Introduction

The Multi-Party Interim Appeal Arbitration Arrangement (MPIA) was established as a temporary measure to address the crisis caused by the dysfunction of the WTO’s Appellate Body, largely instigated by the United States. Historically, parties dissatisfied with a WTO panel report could appeal to the Appellate Body under Article 17 of the DSU. In such cases, the panel report would not be adopted by the Dispute Settlement Body (DSB) as per Article 16.4 of the DSU. The Appellate Body had the authority to “uphold, modify, or reverse” the panel’s legal findings (under Article 17.13), and its reports were to be unconditionally accepted by the parties and adopted by the DSB (under Article 17.14). However, with the Appellate Body no longer functioning due to a lack of judges, a party can now obstruct the conclusion of a case by appealing a panel report to the non-functional Appellate Body, effectively preventing its adoption by appealing “into the void”, thereby impeding enforcement rights. This tactic was exemplified by USA itself in its recent dispute with China in United States – Origin Marking Requirement.

The MPIA seeks to circumvent this issue by preventing disputes from being appealed into the void, while ensuring that panel reports remain enforceable. Without a legally binding Appellate Body report adopted by the DSB, winning parties cannot enforce their rights under WTO law, thereby leaving disputes unresolved and rights unenforced. Consequently, disputes would remain “frozen” until either an amicable resolution is reached or the Appellate Body becomes operational again. Despite its intention as a temporary fix, the MPIA has a few systemic and constitutional fallacies, that raise questions about its ability to effectively replace the Appellate Body, which is often regarded as the WTO’s ‘crown jewel.’

Background & Inception of the MPIA

In October 2018, the United States halted the appointment of new members to the Appellate Body, reducing its membership to just three. As these members’ terms expired, the Appellate Body became inactive due to the absence of a quorum, as is stipulated by its rules. The United States continues to block new appointments to the WTO Appellate Body, thereby ensuring its non-functional status. The primary concerns include the Body’s alleged overreach in creating rules beyond the original intent of the agreements, its establishment of influential precedents for future cases, and procedural issues like taking on new cases without resolving the existing backlog.

Therefore, and in response to the standoff initiated by the USA, 16 WTO members joined forces in 2020 to create the Multi-Party Interim Appeal Arbitration Arrangement (MPIA), serving as a temporary solution to overcome the deadlock. Over time, additional countries have joined this alternative system, now totalling 52 members, including the EU member states, collectively representing a substantial share of global trade.

Objective & Functioning of the MPIA

The Multi-Party Interim Appeal Arbitration Arrangement (MPIA) operates under Article 25 of the Understanding on Rules and Procedures Governing the Settlement of Disputes (DSU). This article is unique among the DSU’s arbitration provisions, as it allows WTO members to use arbitration independently for dispute settlement. In contrast, arbitration under Articles 21.3(c) and 22.6 is only available when used in conjunction with litigation.

As an interim appeal arbitration procedure, the MPIA enables members to bypass the standard appeal process detailed in Articles 16.4 and 17 of the DSU and facilitates the use of the arbitration mechanism instead (Article 25), which provides disputing parties with significant autonomy and procedural flexibility, allowing them to draft or specify rules of conduct tailored to their specific interests. Further, under the MPIA framework, the panel procedures remain consistent as per the DSU provisions, while appeals are governed by the MPIA. Annex 1 of the MPIA delineates the framework for the appeals process, which, while constraining the extent to which disputes can be individualized in comparison to ad-hoc arbitrations, still grants arbitrators sufficient discretion to adjudicate issues deemed “necessary for the resolution of the dispute.” This also goes to address concerns regarding overreach, as highlighted by the United States, by ensuring that the scope of arbitration remains focused yet flexible enough to resolve the core issues of the dispute effectively. Moreover, compliance with the DSU is still required, as certain mandatory provisions cannot be disregarded. This is evident from Article 3.5 of the DSU, which mandates that arbitral awards must conform to WTO law, thereby precluding the selection of conflicting legal standards. Furthermore, arbitral awards issued under the MPIA are subject to the same implementation oversight (Article 21) and the compensation & suspension of concessions framework (Article 22), which extends these provisions to arbitral awards in a similar manner.

This arrangement guarantees that disputes can continue to be resolved through arbitration, thereby preserving the functionality of the WTO’s dispute settlement system despite the ongoing challenges with the Appellate Body. Nevertheless, the new system has its own set of limitations, which will be examined in the following discussion.

Issues With the Multi Party Interim Arrangement

– Legal Nature of the MPIA:

The legal status of the MPIA is ambiguous, raising questions about whether it operates within or outside the WTO framework. Given that the MPIA is based on Article 25 of the DSU, which permits arbitration, it can reasonably be inferred that the MPIA is fundamentally anchored to the DSU since its inception. Additionally, it’s notification to the DSB as an addendum to the “Statement on a mechanism for developing, documenting and sharing practices and procedures in the conduct of WTO,” further hints at the MPIA’s integration into the WTO system.

One clear aspect of the MPIA is its voluntary nature and the mutual agreement required for the adoption of arbitral awards. However, the issue of whether these awards set a precedent remains contentious, especially with opposition from the United States, which will be dealt with in further sections of this paper.

To date, the MPIA has issued one award in the case of Colombia – Anti-Dumping Duties on Frozen Fries from Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands. Prior to this, an ad hoc appeal-arbitration issued an award in Turkey – Certain Measures Concerning the Production, Importation, and Marketing of Pharmaceutical Products. Although Turkey is not an MPIA member and this award is not officially classified as an MPIA award, it is significant because it was the first WTO appellate decision under Article 25 arbitration during the Appellate Body crisis. This is also significant as it demonstrates the MPIA’s success in maintaining the system’s “binding character and two levels of adjudication.” However, the primary concern is evaluating how effective this appeal mechanism will be in practice over the long term.

Expanding on the discussion, it’s worth noting that the MPIA might even be on a trajectory to assume an even more binding authority than the Appellate Body. Unlike the Appellate Body, whose decisions become binding only after being adopted by the Dispute Settlement Body (DSB), the MPIA renders its decisions binding without requiring DSB adoption. This effectively prevents parties from rejecting the awards issued by the MPIA. Furthermore, while the MPIA possesses the authority to “modify and reverse” Panel reports – power similar to that of the Appellate Body – the critical question remains whether the MPIA is sufficiently formalized to surpass the Appellate Body’s mandate and maintain its practices. This situation raises concerns about potentially undermining the foundational structure of the WTO’s Dispute Settlement system. This threatens the very structure of WTO Dispute Settlement.

– Controversial Constitutionality:

The constitutional stature of the MPIA also stands flawed. A significant flaw in the MPIA is the requirement for parties to forgo the appeal mechanism established under Article 16 of the DSU to proceed with arbitration under Article 25. Requiring parties to relinquish their right to appeal simply to have their case heard highlights a constitutional weakness in the arrangement, as it opens the door to potentially ineffective adjudication.

Further, the current structure of the MPIA stipulates that an arbitration award is binding only on the parties involved in the specific dispute. These awards do not bind other WTO members nor the same parties in future disputes. However, the preamble of the MPIA emphasizes the importance of “consistency and predictability in the interpretation of rights and obligations under the covered agreements,” suggesting a potential precedential value. Despite the potential benefits of treating these awards as precedents, it remains uncertain whether this can occur without formal adoption by the WTO Membership. Dispute Settlement Body (DSB) reports, even with limited precedential value, after all are respected for their persuasive authority rather than binding precedent. However, recently the arbitrators in the Turkey and Columbia cases referenced prior Appellate Body reports to interpret the DSU and GATT provisions. Given the inherent ambiguity of international agreements, it is challenging to envision an award that does not rely on or draws parallels with previous international decisions.

The MPIA does not explicitly state whether its arbitration awards should serve as legal precedents within the WTO framework. While the preamble underscores the necessity for predictable and consistent interpretations of WTO rights and obligations, it also maintains that MPIA arbitration decisions cannot alter or diminish the rights and obligations established under the WTO Agreement and other covered agreements. This reflects a delicate balance: there is a recognized need for stable legal interpretations, but a cautious approach is taken to avoid expanding members’ obligations through arbitration, again hinting at the fragile nature of this mechanism. Given the current paucity of MPIA cases, it is difficult to determine the extent to which precedential practices will be adopted.

Unlike Appellate Body (AB) reports, which are typically adopted due to a negative consensus (where they are almost always accepted), MPIA arbitration awards do not require formal adoption by the DSB. This raises significant questions about the role of MPIA awards in WTO jurisprudence. Since these awards are not formally adopted by the DSB, their contribution to WTO case law might differ from that of AB reports. Furthermore, the argument that the absence of formal adoption should prevent MPIA awards from influencing WTO jurisprudence is not particularly compelling. A more substantial issue is that MPIA decisions are not founded on the established rules of the WTO, which could be a more significant factor in determining their impact on the broader legal framework of the organization. This situation creates an interesting dynamic, as the MPIA aims to provide consistency and predictability while navigating the limitations and potential of its legal influence within the WTO system.

Challenges in Procedural Compliance and the Role of Key States:

The working procedures for appellate review within the WTO have been clearly established, but adherence to these procedures has been inconsistent, particularly by the architects of the current dysfunction. Notably, in its dispute with China, the United States appealed the Appellate Body (AB) report without filing a written submission outlining the grounds for appeal. This action contravened Rule 21(1) of the Working Procedures for Appellate Review, which mandates that parties must file a written submission specifying their grounds for appeal and provide a copy of the same to the other party. This failure to honour established procedural rules underscores the broader issues of compliance and respect for the established norms within the WTO’s dispute resolution framework, especially being undermined time and again, by the US.

Unilateral Trade Measures and Their Impact on Energy Policy:

Another issue, which isn’t an inherent issue of the MPIA, but revolves around the gaining popularity and imposition of the MPIA on the member states to prevent them from appealing into the void, is that some states have started issuing retaliatory measures to the parties to the dispute, who pursue empty appeals to the defunct appellate body. This can be substantiated by the retaliatory measures taken by the European Union in February 2021 based on the revised regulations and by Brazil in January 2022. These unilateral sanction threats not only force other WTO members to accept the MPIA, but they also violate the prohibition of unilateral measures spelled out in Article 23.1 of the DSU. Such practices do not set a good example for the rest of the member states and in no time, we’ll see others following in the same suit.

In January 2022, Brazil imposed sanctions on countries engaging in appeals “into the void,” targeting members who bypass the WTO’s defunct Appellate Body by opting out of the MPIA. Though initially focused on trade, Brazil’s sanctions hint at the broader, emerging trend of punitive measures that could extend into specific domestic sectors, including renewable energy policies. Such actions reveal a growing willingness among MPIA proponents to enforce compliance through anticipatory retaliation, thereby discouraging states from using void appeals to avoid MPIA jurisdiction. Brazil’s stance exemplifies the pressures faced by non-MPIA members, illustrating how trade measures can be wielded as a tool to prompt participation or adherence to the WTO’s temporary mechanisms.

Beyond trade, this trend could reshape state-level incentive policies, particularly in sectors like renewable energy, where incentives are crucial to achieving both national and global climate goals. Faced with potential sanctions, some states may reconsider or even roll back renewable energy subsidies to avoid retaliatory action, prioritizing stable trade relations over sectoral advancements. Developing nations, in particular, may experience heightened vulnerability, as they often rely on renewable incentives to transition to low-carbon economies but lack the economic resilience to endure trade penalties.

This unintended deterrent effect illustrates a pressing need for clear guidelines on retaliatory practices within the WTO framework, especially as they increasingly intersect with state policies that have broader social and environmental objectives. Without consistent regulations, anticipatory retaliations risk creating a policy landscape where trade enforcement clashes with global sustainability goals, leaving states caught between compliance with trade demands and commitments to critical incentive-driven sectors.

Conclusion and Suggestions

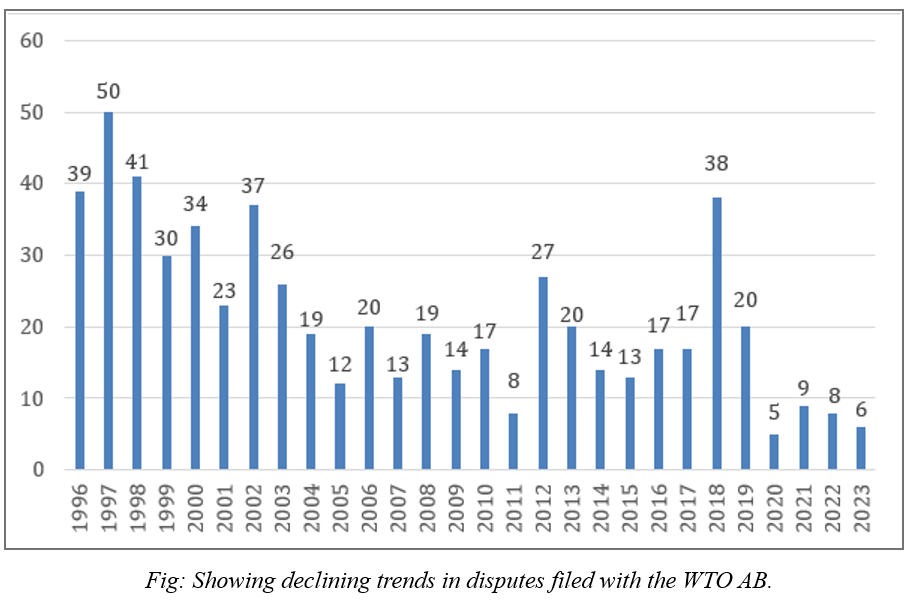

The paralysis of the Appellate Body has introduced significant uncertainty into the WTO dispute settlement system. In response, members have turned to the appeals process outlined in Article 25 of the DSU. It could be hoped that the Appellate Body’s absence will draw attention to the advantages of having a working system for resolving trade disputes that includes the need for a strong appellate review process. Although the WTO’s dispute settlement system and the MPIA could use some improvement, it is hoped that Members would quickly come to consensus regarding the changes they want to bring about so that the system can move towards some light and certainty. For all the enthusiasm the preceding several years have generated, it is nothing compared to the real danger of either having a broken WTO dispute settlement system or none at all. Moreover, as suggested by Henry Gao, if the General Council enforces majority voting to appoint the members of the Appellate Body instead of the DSB practice of reverse consensus, betterment of the situation could still be hoped for. However, since member states are not very inclined towards voting in the first place, and as no one wants to oppose the US, no end of the failure of the Appellate Body seems to be in sight. Member states seem to be losing faith in the WTO Dispute Settlement mechanism (as can be seen by the following figure) which can be seen as a direct consequence of threatened authority of the Appellate body.

Despite its criticisms of the Appellate Body for being unfair and not aligning with the interests of the U.S. and other WTO members, the U.S. recently engaged in a hypocritical move by appealing its dispute with China into the void it helped create.

It would be worth mentioning that despite its well-intentioned design, the MPIA, with its numerous constitutional and practical shortcomings, is unlikely to become the anticipated remedy for the Appellate Body’s issues. In fact, it may exacerbate existing problems rather than resolve them. The MPIA, itself hinged to the WTO framework, could set a troubling precedent by establishing an appeal mechanism outside the WTO, and it might foster a misleading sense of optimism that diminishes the political resolve among WTO Members to seek a viable solution. Unless Members can overcome their reluctance to engage in voting—a process explicitly sanctioned by the WTO Agreement—they are unlikely to achieve a lasting resolution, particularly in the face of challenges from the US or other Members with similar inclinations. Meanwhile, as they await a seemingly elusive resolution, the valuable progress achieved over the past 25 years may be at risk of being undone.

About the Author:

Mansi Khanna, Legal Officer with the Government of Scotland

Editorial Team:

Managing Editor: Naman Anand

Editor in Chief: Faraz Khan

Senior Editor: Tisa Padhy

Associate Editor:

Parmi Banker

Junior Editor: Haripriya Gautam

Recent Comments