Abstract

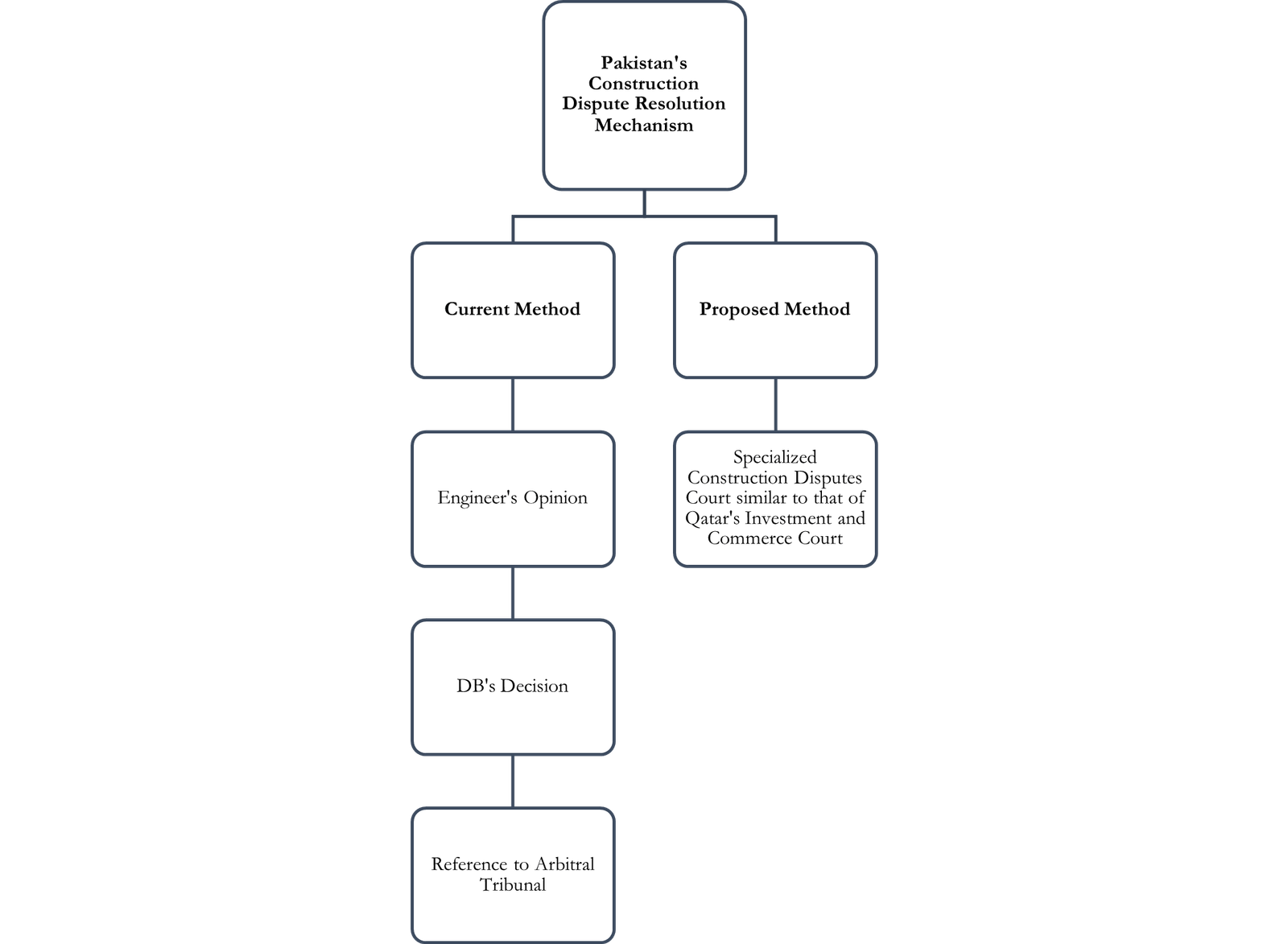

The construction industry in Pakistan is governed by the Fédération Internationale Des Ingénieurs-Conseils (FIDIC) Construction Contracts, with construction disputes being typically resolved through the use of an Engineer, a Disputes Board, or construction arbitration. However, this system faces various issues ranging from corruption to expensive fees. To address these challenges and improve the efficiency of the construction dispute resolution mechanism, the Authors propose that Pakistan adopts a system similar to Qatar. Qatar recently introduced a specialized Investment and Commerce Court. This Court boasts advanced electronic systems, shorter deadlines for decisions, and the ability to appoint experts and enforce judgments. Implementing a similar system in Pakistan could improve the construction industry and overall business environment.

Introduction: Construction Dispute Resolution in Pakistan under the FIDIC Regime

In Pakistan, domestic arbitration is governed by a single legislation, i.e., theArbitration Act 1940 (hereinafter the “1940 Act”). Construction works are governed by the conditions of theFédération Internationale Des Ingénieurs-Conseils (FIDIC) Construction Contract. The most utilized version is the1987 edition (amended up to 1992) of the Red Book for Government-funded construction projects and the2010 Multi-Development Bank Harmonized Edition (Pink Book) for internationally funded construction projects.

Further,the 1987 Red Book has been given increased sanctity and recognition by thePakistan Engineering Council (PEC). The PEC modified and adopted the conditions from the 1987 Red Book in thePakistan Engineer Council Standard Forms of Civil Works on 11 July 2007. Additionally, it is noteworthy that the FIDIC Regime in Pakistan is bolstered by the Constructors Association of Pakistan, whose members undertake85% of Pakistan’s infrastructure development projects.

The dispute resolution mechanism for construction projects under the FIDIC regime of Pakistan is primarily arbitration, which hasgained pace in the past two decades. Further, Pakistan’s involvement in theChina-Pakistan Economic Corridor has led to the integration of specialized principles and concepts in Pakistan’s construction dispute resolution mechanism. Additionally, specialized professionals (with engineering and legal backgrounds) have begun to participate in the system as arbitrators, increasing the growth and development of construction arbitration in Pakistan.

1. Conundrums Associated With Construction Dispute Resolution Clauses in FIDIC Standard Conditions of Contracts for Construction Projects in Pakistan

There are several dispute resolution clauses in multiple FIDIC Standard Conditions (hereinafter “Standard Conditions”) of contracts for construction projects that are discussed below.

According toClause 67 of the Standard Conditions in the 1987 Red Book, any construction dispute related to an agreement must be referred to a supervisory authority, i.e., the “Engineer,” for his “determination,” i.e., for his opinion. After the Engineer’s determination, the dissatisfied Party can refer the matter before the Engineer for his “decision,” wherein the Engineer is supposed to make his decision within 84 days of receiving the matter. If a Party is dissatisfied with the Engineer’s decision or the Engineer fails to arrive at a decision in 84 days, the dissatisfied Party can issue a Notice of Intention to proceed to Arbitration to the other Party.

Although the Standard Conditions stipulate a specific number of arbitrators and their method of appointment, these conditions are generally substituted by the specific conditions of a construction contract that essentially imposes an obligation on the Parties to adhere to the arbitration methods mentioned in Pakistan’s 1940 Act.

However, thereare varying degrees of criticism from various stakeholders regarding the powers of an Engineer because it is not feasible to expect an Engineer to give a Determination for a matter. After all, an Engineer is required to obtain their employer’s approval. After the determination, an Engineer is expected to give a different “Decision” as an independent and impartial adjudicator. This was again seen as unfeasible as an Engineer is answerable to their employer.

In response to these criticisms, the powers of an Engineer were partially stripped away by the formation of the Dispute Adjudication Board (hereinafter “DB”). In the Standard Conditions mentioned in the1999 Red Book, after an Engineer determined a matter, the dissatisfied Party could refer it to the DB for its “Decision” instead of the Engineer.

The DB is constituted of a single member or three members mutually decided by the Parties, wherein the third member acts as the umpire. Clause 20.6 of the Standard Conditions in the 1999 Red Book states that if the decision of the DB is unsatisfactory, the dissatisfied Party can issue a Notice of Intention to initiate arbitration proceedings. Therefore, the DB significantly increases the chance of dispute resolution before the matter is referred to arbitration. It is also noteworthy that a similar DB-related dispute strategy was reiterated in thePink Book under sub-clause 20.2.

However, it is imperative to note that construction disputes in Pakistanare seldom resolved before arbitration proceedings since Engineers and the DB are not appointed independently, thereby violating the spirit of the Standard Conditions. This is because the employers are made a Party to the FIDIC agreements, due to whichthey impose their choice of Engineers for determination and as members of the DB for decision. This impacts the credibility of the DB, andit inevitably results in the dispute being referred to an independent Arbitral Tribunal wherein the arbitrators are independently appointed by the Courts.

Thus, it is observed that the dispute resolution mechanism where an Engineer’s opinion is followed by a DB’s decision is often rendered unfair, counterproductive, and time-consuming because of corruption.

2. New Dispute Resolution Mechanism in Qatar: Investment and Commerce Court

In May 2022, a specialized Investment and Commerce Court was introduced in Qatar. An essential step in developing its judicial system, the move is expected toaccelerate the pace of dispute resolution, ultimately making Qatar an attractive business destination for foreign investors.

Commercial disputes often take years to resolve and can muster enormous costs for the Parties involved. Unsurprisingly, this makes for a discouraging business environment for investors. Construction dispute resolution requires the involvement of experts and judgeswith considerable technical and commercial experience to understand the intricate legal and technical issues at hand. Thus, forming a specialized Court for dealing with matters like these was a step in the right direction.

The specialized Court was established by way ofLaw No. (21) of 2021. This Law has granted the specialized Court jurisdiction over disputes related to commercial contracts, commercial papers, commercial assets, and disputes arising between partners or shareholders in commercial companies and those between merchants. Such disputes could involve intellectual property, maritime sales, bank operations, commerce transactions, mortgages, insurance, transport and supply contracts,building and construction contracts, etc.

A. Administrative Structure

The Investment and Commerce Court has its independent headquarters, equipped with the latest electronic means, and an independent budget whose spending is determined by its President. The President is appointed by the Supreme Judicial Council and is a judge with a rank no less than a Vice President of the Court of Appeal.

The Court contains two levels: the Circuits of First Instance and the Circuits of Appeal. The Supreme Judicial Council appoints the judges for both circuits. As laid down in Article No. 5 of Law No. (21) of 2021, the Circuits of First Instanceare composed of three court judges, headed by their senior-most member. This Court is competent to consider all cases with a value exceeding 10,000,000 Riyals. Similar to the Circuits of First Instance, the Circuits of Appeal are composed of three judges headed by their senior-most member. They adjudicate upon the appeals from orders and judgments of the Circuits of First Instance. Their judgments are final and unappealable.

The Supreme Judicial Council may delegate someone from the judges of the Circuits of Appeal to chair a Circuit of First Instance of the Court for a term of 1 year, renewable for a similar period.

B. Other Notable Features

Some of the other significant features of the specialized Court are as follows:

i.Appointment of experts: Under Article No. 33 of Law No. (21) of 2021, the Court may depute an expert if it is deemed necessary in a particular dispute. The expert is expected to submit their report electronically within sixty days. Further, the Parties are allowed to give their comments on the report within fifteen days.

ii.Enforcement judges: The enforcement of judgments rendered by the Court is carried out under the supervision of “enforcement judges.” They are appointed by the Supreme Judicial Council for one year and have the jurisdiction to entertain substantive disputes in addition to passing enforcement orders.

iii.Summary judges: The Court has been vested with the jurisdiction to settle summary commercial actions. Judges appointed by the President may temporarily adjudicate in summary actions where there is fear of the lapse of time and issue writs on tentative Orders and Petitions. Appeals against judgments in summary actions and writs of petitions must be decided within seven days from the date of notifying the concerned persons.

iv.General assembly: The Court has a general assembly governed by the same provisions for general assembliesin the judicial authority law. The assignments of members in different departments are done by the President, which is based on the proposal of the general assembly.

v.Electronic system: The Law establishes a digital system for all the proceedings. This means the registration of lawsuits, submission of documents, appeals, claims, grievances, requests, etc., will be done electronically. This advanced system is expected to reduce the burden on Courts and provide increased efficiency.

vi.Deadlines: Law No. (21) of 2021 prescribes shorter timelines for decisions regarding appeals and judgments. While the Law related to the Proceedings states that an appeal against summary judgments should be preferred within twenty days, this Law has laid down a deadline of seven days for the same. Further, the period prescribed for appeals in this circuit is fifteen days from the date of notifying the concerned Parties, as opposed to the period provided for appealing the judgments issued by the Civil Court of First Instance, which is 30 days from the date of judgment. The law also requires preliminary rulings to be passed within ten days starting from the date of the case being referred to the circuit. With the object of speedy rulings in mind, adjournment of lawsuits more than once has also been made impermissible. Most importantly, all disputes must be settled by the circuits within90 days from the date of referral, with a 45 days extension permitted in certain cases.

3. How Pakistan can benefit from Qatar’s footsteps

As discussed earlier, Pakistan’s current construction dispute resolution mechanism is not ideal. The DBlacks credibility since its members are not appointed independently but by government departments that are themselves Parties to the FDIC agreements.

In addition to the rampant corruption, another issue that needs to be addressed is the slow disposal of cases.Research has shown that a significant issue is the number of visits litigants must make to Pakistani courts. An average of seventy-two visits must be made by a Respondent for the case to be finished, which could cost as much as Rs. 2,70,000. Moreover, even if a judgment is passed reasonably quickly, itsexecution can still take years.

While there are several types of special Courts in Pakistan for dealing with matters liketerrorism,labour,drugs,environment,banking,gender-based violence, and other matters, no such Court has been established for handling construction disputes. Thus, the Authors propose the following change in Pakistan’s current construction dispute resolution mechanism:

From the aforementioned, the Authors attempt to convey that the process of seeking an Engineer’s Opinion followed by a DB’s decision should be replaced with that of a specialized Court. The reasons for the same shall be discussed below.

The Investment and Commerce Court in Qatar is a specialized court explicitly designed to handle commercial and investment disputes, making it well-suited also to resolve construction disputes that may arise in the construction sector. The Court has several features that make it an attractive model for Pakistan to consider in its dispute resolution system.

One key feature of the Investment and Commerce Court is its electronic system, which allows for the electronic registration of lawsuits, submission of documents, and other proceedings. This advanced system is expected to reduce the burden on the Court and increase its efficiency. Implementing a similar system in Pakistan could help to streamline the construction dispute resolution process and make it more efficient, saving time and resources for all parties involved.

Another advantage of the Investment and Commerce Court is its shorter deadlines for decisions. Compared to other Courts in Qatar, the Investment and Commerce Court has shorter timelines for appeals and judgments and deadlines for preliminary rulings. Thus, a faster decision-making process can help to resolve disputes quicker, reducing the overall time and cost of the construction dispute resolution process in Pakistan.

Additionally, the Investment and Commerce Court also has the power to appoint experts and enforce judgments. This can be particularly useful in construction disputes, where technical expertise is often required to assess the merits of a case. The ability to appoint experts allows the Court to consider specialized knowledge when making decisions. At the same time, the power to enforce judgments helps ensure that the Parties follow through on any agreements or decisions made.

Another novel element of the Investment and Commerce Court in Qatar is its general assembly. The general assembly is responsible for assigning members to different departments of the Court and is presided over by the President of the Court. The general assembly can be a valuable feature for Pakistan to consider in its construction dispute resolution system, as it allows for the participation of a diverse group of stakeholders in the decision-making process. Pakistan could benefit from the input and expertise of many individuals, including construction industry professionals, legal experts, and representatives from government agencies or other organizations. Including these stakeholders in the general assembly would allow for a comprehensive and well-rounded approach to resolving disputes.

In addition, the general assembly could also provide an opportunity for transparency and accountability in the dispute resolution process. It could help ensure that decisions are fair and unbiased. This could help build trust and confidence in the system to tackle the problem of credibility.

Under the current method, it is imperative to note here that after a matter is referred to an Arbitral Tribunal, the Parties continue to suffer because of the following primary reasons:

i. Delays in the resolution of disputes: The arbitration process can take a significant amount of time, leading to delays in the completion of the construction project. This can be especially problematic if the dispute involves issues that need to be resolved before work can continue.

ii. Lack of finality: It can be difficult to enforce arbitral awards, especially if one of the Parties refuses to comply with the terms of the award. In some cases, arbitration may not provide a final resolution to a dispute, as Parties may be able to appeal the arbitral award. This can also lead to additional costs for the Parties involved.

iii. Difficulty in selecting construction dispute specialized arbitrators: Parties may have difficulty agreeing on the selection of an arbitrator who specializes in construction disputes or possesses technical knowledge in similar sectors. This may be because of multiple reasons, such as the unavailability of specialized arbitrators, questionable credentials, lack of experience despite possessing technical knowledge on construction disputes, and other similar reasons. Thus, this can lead to inordinate delays in the arbitration process and may affect the perceived impartiality and independence of the arbitrator.

Therefore, if specialized Courts for construction disputes are introduced, they shall eradicate the inevitable need for reference to Arbitration, saving Parties’ resources, increasing project completion timelines, and would benefit other elements in the construction sector.

4. Conclusion

Qatar’s Investment and Commerce Court is a well-developed and efficient system for resolving commercial and investment disputes. By implementing a similar system, Pakistan could benefit from the Court’s advanced electronic system, shorter deadlines, and the ability to appoint experts and enforce judgments. These features would be particularly useful for the construction sector in Pakistan, where disputes can be complex and require specialized knowledge.

By adopting a system similar to the Investment and Commerce Court, Pakistan could improve the efficiency and effectiveness of its dispute resolution process, helping to resolve disputes more quickly. This would benefit all Parties involved in construction projects in Pakistan, including contractors, developers, and clients, as it would reduce the time and cost of resolving disputes and allow for a more seamless construction process. Ultimately, implementing a system like the Investment and Commerce Court in Qatar could help strengthen Pakistan’s construction industry and improve the country’s overall business environment.

About the Authors

Mr. Pushpit Singh is a 4th year BBA. LLB student from Symbiosis Law School, Hyderabad, and a Senior Editor at IJPIEL.

Ms. Ria Goyal is a 3rd year student from Maharashtra National Law University, Mumbai, and a Junior Editor at IJPIEL.

Editorial Team

Managing Editor: Naman Anand

Editors-in-Chief: Jhalak Srivastav and Muskaan Singh

Senior Editor: Aribba Siddique

Associate Editor: Tisa Padhy

Junior Editor: Apoorv Vats

Preferred Method of Citation

Pushpit Singh and Ria Goyal, “Laying the Foundation for Effective Construction Dispute Resolution: Lessons for Pakistan from Qatar” (IJPIEL, 23 January 2023)

<https://ijpiel.com/index.php/2023/01/23/laying-the-foundation-for-effective-construction-dispute-resolution-lessons-for-pakistan-from-qatar/>

Recent Comments