As of 2023, India’s renewable energy market is pegged at aroundUSD 22 billion, estimated to reach approximatelyUSD 240 billion by 2032 at a CAGR of 8.71%. Its ambitious emissions targets will require that at least 50% of its current energy needs are met by renewable or sustainable energy sources by 2030 – which translates to an installed renewable capacity of 500 GW, as against the current capacity of 179 GW.

The need for capital in such a market is self-explanatory. In this context, secondary markets and capital recycling become key tools, allowing individual investors to find easy exit opportunities, while patient capital fills the gap. The funds realized can be then used towards the development of new projects. However, creating such markets requires the aggregation of projects to streamline the process of trading ownership interests in infrastructure projects. Infrastructure Investment Trusts (InvITs) were introduced by SEBI as vehicles for easing this process of capital recycling and market-making.

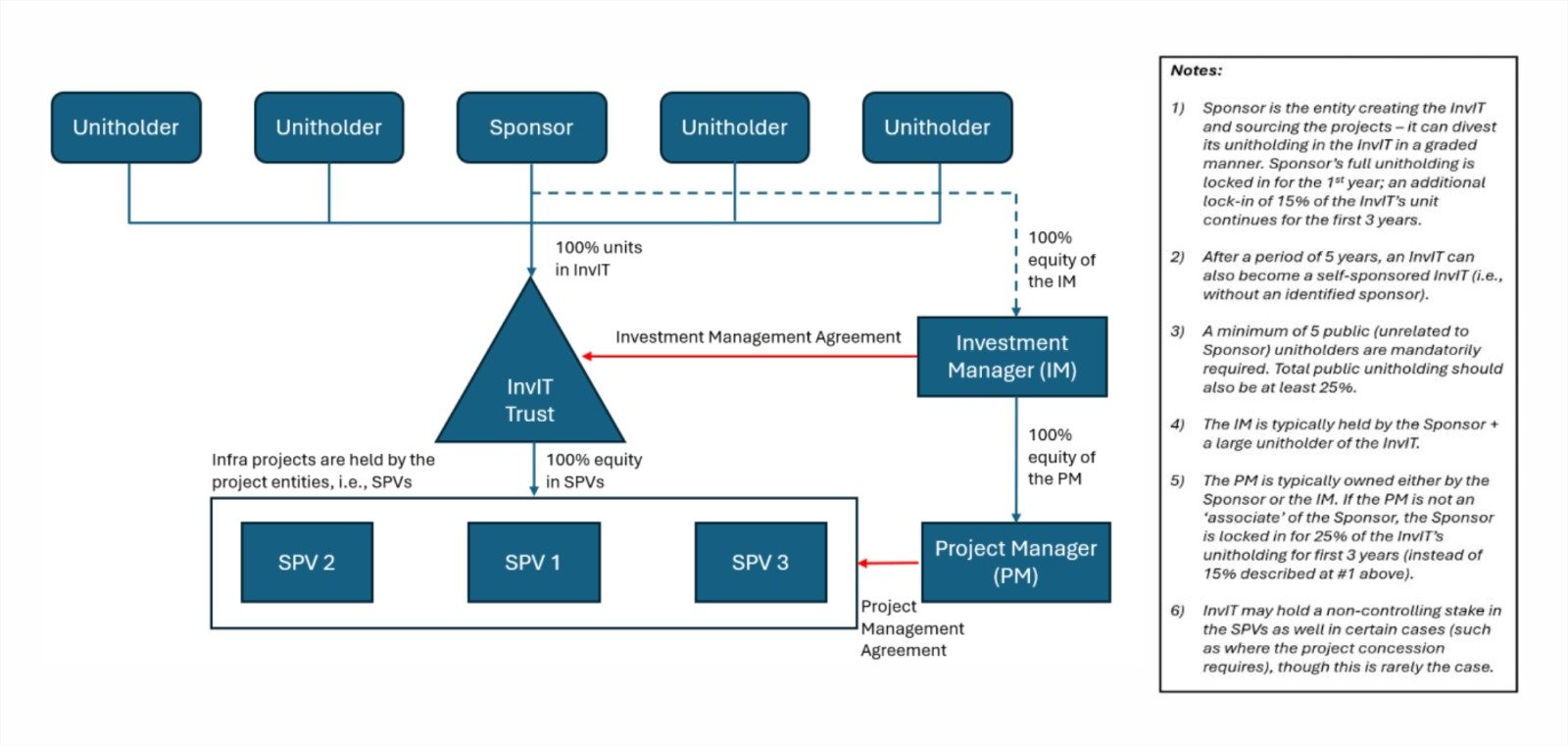

At the risk of an over-simplification, InvITs are holding entities for multiple infra projects. Once a project becomes revenue-generating, the developer can sell its ownership of the project to the InvIT and the InvIT contracts the day-to-day management to another entity for a fee and distributes returns to its investors from the revenue generated by the projects in its portfolio. A typical InvIT structure is provided below.

By selling a constructed project to the InvIT, the developer gets an immediate cash realisation on its investment, which can then be used to build new projects. At the same time, financial / retail investors, who may lack resources to scout, diligence and invest in individual projects can invest in a professionally managed project portfolio which is generating a return from day 1. Though a similar structure can be achieved in a holding company as well, key differentiators of an InvIT are summarized below.

|

S.No |

Parameter |

InvIT |

Holding Company |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Governance Structure |

Managed by the IM which is typically controlled by the Sponsor and large unitholders. |

Managed by the board of directors of the holding company itself. |

|

2 |

On-lending to Project SPVs |

Permitted – thin capitalization rules don’t apply. Therefore, the interest charged to the Project SPVs can be expensed by the SPV, allowing a more tax-efficient funding structure for the projects. |

Permitted, albeit to a limited extent. Two considerations apply:

|

|

3 |

NBFC / CIC Risk |

Does not apply. |

If more than 50% of a company’s assets are in the form of financial assets; and income from such assets constitutes more than 50% of the total income, the holding company is deemed to be a non-banking finance company (NBFC). |

|

4 |

Tax Pass Through |

Full pass-through status – all income accruing to the InvIT from the Project SPV (in the form of capital gains and interest) is taxed directly at the hands of the unitholder. |

No pass-through – income accruing from the Project SPV is first taxed at the prevailing corporate tax rate at the holding company. Further tax accrues when transferring the investment to the ultimate investors. |

The interest cost savings discussed in point #2 above, combined with the removal of the additional tax layer described at point4 above meaningfully enhance the investment value realised by the investor. These incremental returns are what have made InvITs such a lucrative proposition for large pension funds and sovereign wealth funds to invest in tolling or operating Indian infrastructure, freeing up more aggressive strategic capital of the developers which would otherwise have been tied up in these projects for decades. This capital recycling cycle, enabled by a rollover of assets into InvITs to more patient capital has demonstrated a visible change in the roads sector already, which has seen a CAGR of 18% (YoY) since InvITs were first introduced. The success of this model is also evident in the fact that recently, the government has taken a decision. to divest its holdings of certain road assets solely to InvITs.

A similar story can play out in the renewables space as well. However, for this to take place, certain sectoral challenges still need to be resolved. These are:

-

DISCOM risks: The consumer for a power generating entity is the power distribution company (known as DISCOMs). These are entities that acquire the ultimate consumers (individuals, factories, etc.) and then supply power to the last mile. However, Indian DISCOMs have been financially constrained due to inefficient state-wide monopolies, subsidization of consumers (not reimbursed by the exchequer), etc. This causes concerns about credit-worthiness and risks to reliable cashflows for the power generator.

-

Off-taker-DISCOM risk: As a part solution to the challenges of selling power directly to DISCOMs, the government introduced a system of off-takers, who act as intermediaries among various DISCOMs. Effectively, this passes the risk of the creditworthiness of a DISCOM to the off-taker. The power generating company enters into an agreement with an off-taker and the off-taker eventually sells power to the DISCOM. Ideally, if one DISCOM fails to pay its dues, the off-taker can make future sales to another DISCOM and ensure consistent cashflows. However, this has created a multitude of new issues. First, DISCOMs across the country are in distress and therefore, the liquidity sought to be enhanced by aggregating them at the off-taker level has not resulted in the desired outcomes. Second, since DISCOMs are virtually state-based monopolies, cutting off supply even in the face of delayed payments is a political hot potato, as it effectively means blacking out an entire state. Therefore, in practice, DISCOMs rarely lose access regardless of delinquencies. Third, the introduction of the off-taker as an intermediary has complicated the liability matrix and created a host of disputes where the off-taker attempts to pass on the delay or discounted payments made by DISCOMs to the power generating company, highlighting that practically, the contracts are inter-linked and the cushion sought to be introduced may not work in practice.

-

Regulatory risk: Unlike the roads sector, there are several regulatory ambiguities in this space which are yet to be resolved. These concern disputes around the ‘must-run status’ (since consumption patterns differ during the course of a day or seasons, there are times when the grid has surplus power requiring power plants to shut down or not sell their power to prevent the grid from getting destroyed. This is a loss to the generating company and there are multiple disputes about how this loss can be passed on to the off-takers orDISCOMs, and calculations of the appropriate ‘plant load factor’ which determines the output of a plant and accordingly the revenue received by the plant, among others. These disputes are hyper-technical in nature and caught up in various stages of litigation making a cohesive resolution difficult.

-

Transmission Challenges: Though there has been significant improvement on the transmission of power from the plant to the off-taker orDISCOM’s facility, there are still some lingering challenges in the interface of the various players in the system. For instance, a key industry-wide dispute concerns the payment of penalties to transmission companies (primarily, Central Transmission Utility aka PowerGrid) should a project be abandoned even before its construction. Current regulations are unclear on the quantum of penalty to be paid and the circumstances in which they become payable. For instance, if the project is canceled because the off-taker and the DISCOM cannot agree on a price and no on-ground progress is undertaken on the project, canceling the project can still cause the generating entity to bear the cost of cancellation of the transmission side. These provisions are presently under challenge but there is likely to be a significant time lag in the issue being resolved.

Resolving the above challenges are key in creating monetizable power generating companies which can then be better bundled into InvITs to allow the virtuous capital recycling cycle to move further. A number of renewable focussed InvITs have come up in the recent past, the most prominent being the Mahindra Susten InvIT, funded primarily by the Canadian Pension Fund, Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan Board with the Mahindra Group serving as the strategic project acquirer.

In summary therefore, the key benefits associated with InvITs and challenges impeding their deployment in the renewable energy space can be laid out as follows:

Benefits

-

Allow developers to recycle capital by selling operational projects to InvITs, freeing up funds for new projects.

-

Provide stable long-term returns for diverse investors like pension funds and insurance companies.

-

Enable aggregation of multiple projects into a single investment vehicle.

-

Juicing up returns using leverage without thin capitalisation complications

-

Tax pass-through status, enhancing returns for investors.

Challenges

-

DISCOM risks – financial constraints and lack of creditworthiness of power distribution companies.

-

Off-taker risks – issues with the intermediary off-taker model introduced to mitigate DISCOM risks.

-

Regulatory ambiguities around “must-run” status of renewable plants and calculation of plant load factors.

-

Juicing up returns using leverage without thin capitalisation complications

-

Transmission challenges – lack of clarity on penalties for project abandonment.

Resolving these sectoral challenges is crucial to create monetizable renewable energy assets that can be bundled into InvITs. As the government and regulators work to address these issues, InvITs can play a pivotal role in driving India’s renewable energy growth by enabling capital recycling and attracting long-term institutional investments.

About the Authors

Prashant Khurana (Attorney based out of Delhi and advises foreign investors and private equity funds on India focussed M&A, particularly in the infrastructure and technology space) and Lakshay Jain (5th year law student at Jagannath University)

Disclaimer:

views expressed are personal.

Editorial Team:

Managing Editor: Naman Anand

Editor in Chief: Abeer Tiwari and Harshita Tyagi

Senior Editor: Abeer Tiwari (Ad Hoc)

Associate Editor:

Harshita Tyagi (Ad Hoc)

Junior Editor: Anam Sadaf

Recent Comments