Abstract

Cryptocurrency Mining is the process of using computer power to add blocks to a blockchain in order to verify cryptographic transactions and getting rewarded in exchange. This process has been in extreme demand and scrutiny of the public in recent times, due to the worldwide developments in this area. Unfortunately, the process of mining makes use of a vast amount of electricity, along with generating huge amounts of carbon emissions, among its many harmful impacts on the environment, and the absence of proper legal laws in India for this process just adds to the trouble. This article aims to analyze the hurdles of cryptocurrency mining in India, considering the environmental policies and legislation currently in existence, along with analyzing the potential of cryptocurrency mining in India for the coming future.

Introduction

The term cryptocurrency was perfect albeit a bit humorously summarized by the British – American political commentator John Oliver as “Combine everything you don’t know about computers with everything you don’t know about money”. [1] However, to understand this article it is important to at least grasp the basic concept of cryptocurrency.

A cryptocurrency, to put it in very generic terms, is a virtual currency that is backed and secured by cryptography. Cryptography is a method of securing a “message”, where only the sender and the reader can read the contents of the message. For example, if person A sends a message to another person B through a cryptographic platform, then only A and B will be able to read that message. However, if the same message was not secured through cryptography, then the platform through which the message is sent will also be able to access the contents of the message.

Similarly, while making any banking transactions, the bank knows the sender and the receiver of the transaction and also has the knowledge of the details of the transaction. This leaves your transaction vulnerable to prying eyes (read government and hackers). To do away with this, cryptocurrency makes it very difficult for intermediaries (e.g., banks) to know the details of the transaction.

Just like conventional currency is minted through printing mints, cryptocurrencies also have to be mined. The mining process of cryptocurrency is completely decentralized in order to maintain its fundamental structure of network and security.

Put simply, cryptocurrency comes under the domain of blockchain. A blockchain functions when a new block is added to the old block for new transactions, thereby coining the term blockchain. The system also ensures that past transactions cannot be edited or reversed by anyone — granting cryptocurrencies the property of immutability. The user who adds a block is rewarded for adding the block and the quantum of the reward depends on a pre-decided equation. This is cryptocurrency mining in its most basic sense. However, adding a block is a very computer-intensive process. Machines used to add aforesaid blocks are called “Miners”. To make it commercially viable and to stay ahead of the competition, mining facilities have hundreds of miners installed in order to mine cryptocurrency.

Therefore, to summarize it, cryptocurrency mining is a process of using computer power to add blocks to a blockchain in order to verify cryptographic transactions and getting rewarded in exchange.

Environmental Impact of Cryptocurrency Mining

Cryptocurrency mining uses astronomical energy, which works through the proof-of-work blockchains and is the consensus algorithm for the blockchain network. The network involves the opening of a four-number lock, which can have any value from 0000 to 9999. The miner who solves this puzzle earns rewards in the form of Bitcoin. Under this network, the cryptocurrency transactions get recorded by a distributed network of miners, instead of being stored in central common databases. To go through the specialized computers for getting recorded, new blocks need to be created through cryptographic puzzles which intake a huge amount of energy and electricity. [2]

Now, as the price for cryptocurrency increases, the mathematical puzzles become more difficult to solve, and the process of mining becomes less efficient. This trend is especially seen in bitcoin mining. This results in an increased intake of energy and computing power for the same number of transactions in the past, proving to be a major point of concern for environmentalists.

Bitcoins and Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) [3] generate huge carbon emission volumes. Example – A single bitcoin transaction generates a carbon footprint equivalent to 51,210 hours of YouTube or 680,000 Visa Transactions. NFT generates a carbon footprint equivalent to 500 miles of a petrol car drive.[4]

So, where does such a vast amount of electricity come from? – According to the University of Cambridge, 76% of cryptocurrency miners were using electricity from renewables in 2020, which was mainly the result of increased use of computer power with an increase in its prices. [5]

Currently in the world, even though coal, along with other fossil fuels, acts as a major source of electricity, it is equally true that the burning of coal is a major contributor to the increasing risks of climate change. According to a report by the Consumer News and Business Channel (CNBC), bitcoin mining results in a yearly emission of carbon dioxide which is equivalent to approximately 35.95 million tons. [6]

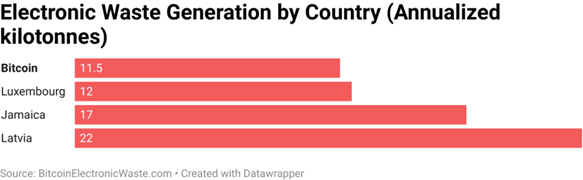

Unfortunately, carbon dioxide emissions are not the only environmental impact of cryptocurrency mining. Mining also results in the collection of huge amounts of obsolete electronic waste, which is especially the case for Application-Specific Integrated Circuits. These are integrated circuits that are specialized in cryptocurrency mining. Example – Bitcoin mining uses specialized singular purpose hardware, which according to a study, becomes outdated every 1.5 years due to the increasing efficiency of newer reiterations of mining devices. [7] This impact has been further reiterated by a Digiconomist who suggests, “For ASIC mining machines there is no purpose beyond the singular task they were created to do, meaning they immediately become electronic waste afterward”. [8]

The above graph is only an indication of the e-waste generated through the disposal of the mining equipment and is not inclusive of other mining facilities, like cooling, which is entrusted to third parties. These too are not capable of being reused and become obsolete in a comparatively faster fashion. [9]

The Changing Trends

While it has been established above that the mechanism of cryptocurrency uses renewable energy and resources to gain efficiency, it is also true that the amount of usage of such renewable energy and resources is hugely dependent on the type of cryptocurrency mining mechanism used by the miners. Therefore, with changing mining techniques, sustainable cryptocurrencies like Chia, IOTA, Cardona, Nano, Solarcoin, and Bitgreen have emerged, which have been identified to be the green alternative to Bitcoin. [10]

Therefore, as it is the Proof-of-work calculations in the mining hardware which is the source of the huge demand of electricity for Bitcoin mining, other mining processes, like ‘farming’ and ‘tangle’ processes, generate similar huge consumption levels without any huge environmental impact. [11]

How India Ranks among the Sustainable Countries for Cryptocurrency Mining

Authors from the DEKIS Research Group from the Catholic University of Avila, Spain, conducted an interesting study for determining the best countries that are capable of carrying out cryptocurrency mining in a sustainable manner (i.e., in the least environmentally damaging manner). [12]

They commenced their study by taking the environmental performance of 180 countries into consideration, as has been provided by the Environmental Performance Index by the University of Yale. [13] This was followed by a study of different factors including:

- The price of electricity

The data was taken from the GlobalPetrolPrices consortium database, [14] according to which the lower the cost of electricity, the better it is for households and businesses. For India, the price highlighted in the graph was 0.077 (kWh, U.S. Dollar) for households and 0.116 (kWh, U.S. Dollar) for businesses in 2020. This electricity cost was inclusive of the various environmental and fuel costs and taxes.

- Amount of energy generated in a sustainable manner

The data was taken from the World Bank database, which had further elaborated the statistics from the International Energy Agency (IEA) and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) statistics. [15] For India, the most recent data available was till 2015, where India only 5.4% of the total electricity production was sourced from renewable sources.

- The temperature

The data was taken from the annual average temperature data (years 1961-1990), as provided by the Climatic Research Unit. [16] It is always better for a country to have lower temperatures, as less energy is spent on the cooling structures. India, being a part of the Northern Hemisphere, noticed a warmer trend, where temperatures saw an increase of about 1.13°C (+/-0.12°C) from the 1961-1990 temperature range.

- The legal regulations

The data was taken from Cointelegraph [17] and Bit2Me [18], wherein India was considered to be a contentious capital-controlling economy that currently has a neutral stance on cryptocurrency mining, considering that no legal regulations are in force.

- The development of the new mining systems

By using the data provided by the World Bank on the country’s expenditure on research and development variable (% of GDP), [19] with an addition of the Human Development Index, India was scaled to be 0.5 on their Human Capital Index (HCI) in 2020. According to the study, the countries that combined higher HDI and higher investment in R&D&I (Research and Development and Innovation) were at an advantage for cryptocurrency mining as they had better facilities and capabilities of performing the mining functions.

The culmination of the study saw Denmark and Germany as the most sustainable countries for cryptocurrency mining, while Bolivia was the least sustainable country. India ranked 87th in this study with a cryptocurrency mining index of 40.8. The main trend in the top-ranking countries was that they were mostly advanced countries with clean energy production, they did not have very high electricity prices, had no legal obstacles stopping from cryptocurrency mining, and most importantly, they invested more in human capital and R&D&I. Another parallelism was that the countries were located in the northern hemisphere, giving them the temperature advantages.

If we analyse this with respect to India, it already has the advantage of being located in the northern hemisphere. However, the price levels of electricity are comparatively higher, with less production from renewable energy sources. Moreover, due to the absence of any legal regulations and clear guidelines, India’s stance on cryptocurrency mining is vague, which does not allow the investors to open themselves to different opportunities in the field.

Hurdles with Cryptocurrency Mining in India

The journey of cryptocurrency in India has not been without its dramatic episodes. The first blow was delivered in 2017 when India banned the import of “ASCI” machines. ASCI machines are used to mine cryptocurrency. The ban forced many mining companies including the Bangalore based blockchain technology company AB Nexus to suspend operations. Following the clampdown on mining activities, In April of 2018, the Reserve Bank of India banned commercial banks from supporting crypto transactions after cases of fraud through virtual currencies were reported. [20]

In March 2020, the Supreme Court of India lifted the ban imposed by RBI. [21] This came as a relief to institutional and retail investors and India-based centralized exchanges like WazirX. However, the lifting of the trading ban by the Supreme Court left a gaping hole from the perspective of cryptocurrency mining as the import ban on ASIC machines was still in place.

The reason for the import ban was quite simple. Mining cryptocurrency is energy intensive. According to an estimate by the Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index, the global activity consumes about 60 terawatt-hours a year (in 2017, the world consumed a total of about 25,000 TWh). [22] The already existing power shortages in India forced the government to take drastic steps. India already suffers from a lack of electricity, with millions of people still without reliable supply.

The second reason could be e-waste. ASCI machines, unlike commercial GPU (Graphical Processing Unit), can only be used to mine cryptocurrencies. With the evolution of technology, these machines become obsolete within a period of 1-2 years as miners prefer newer versions to make the operation more commercially viable. Therefore, the older machines are either sold in the secondary market or dumped down the garbage disposal.

Another obstacle faced by the miners in India is the legal haze when it comes to mining cryptocurrency. Mining of currency, albeit cryptocurrency, can be seen as a government function and not individual venture. [23] Several miners were imprisoned in the year 2017 and since the cases have not been conclusive, it is difficult to paint a clear picture of where the government stands regarding cryptocurrency mining. [24]

Shifting from the legal perspective, it is also clear that it is tough to make cryptocurrency mining feasible in India. Since it is an energy-intensive process, the major overhead cost of the entire project is electricity. In India, the annual cost of electricity ranges between Rs. 5.20-8.20 (around 7-11 cents) per kilowatt-hour on average. To compare it with global standards, the cost of electricity in Kazakhstan is 4-5 cents/kWh. [25]

Just to get a clear perspective on the energy consumption of cryptocurrency mining, Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption, which tracks electricity usage in Bitcoin mining around the globe published that it consumes about 67.29 terawatt-hours a year. [26]

The Government of India has recently reaffirmed its position with regards to the private cryptocurrencies, wherein they have invalidated them as legal tenders and have announced work being done towards the complete elimination of the use of crypto assets in financing the legitimate activities, as part of the payment system. Although being optimistic about blockchain technology in the financial system arena, the Ministry of Finance has proposed the Cryptocurrency and Regulation of Official Digital Currency Bill, 2021, criminalizing possession, issuance, mining, trading, and transferring of crypto assets. [27]

From a trading point of view, India is witnessing a cryptocurrency boom in the country, with 8 million investors holding an estimate of $1.4bn in crypto assets, with new registrations up 30-fold from a year ago. However, under the Liberalized Remittance Scheme (LRS) of the RBI, an individual is allowed to invest only up to $250,000 per year in overseas investment instruments. However, the anonymous identity characteristic makes it impossible for the authorities to track the quantum of intercountry cash flows. [28]

Environmental Policy and its Enforcement in India

It is crucial to take a look at the environmental policy and its enforcement while discussing cryptocurrency mining in India. It is clear up till now that the government of India does not favor cryptocurrency mining and is trying to clamp down on mining as well as trading operations for the last couple of years. However, it is important to dive into the statutory provisions and legislations to understand what laws would mining operations attract even if mining was allowed by the government. A cryptocurrency mining facility can be imagined as a big server room with hundreds of computing units plugged in. Such setups require electricity and cooling solutions to operate, which in turn result in all kinds of pollution.

The environment laws are implemented and enforced by the Ministry of Environment, Forest & Climate Change (“MoEF&CC”), the Central Pollution Control Board (“CPCB”), and State Pollution Control Boards (“SPCBs”) of each of the 28 States and nine Union Territories. Separate regulatory bodies exist for different environmental laws, such as the State-level Environment Impact Assessment Authority, which supervises the Environmental Clearance applications and Environmental Impact Assessment reports; National and State-level Coastal Zone Management Authorities, which supervises the Coastal Regulation Zone (“CRZ”) Notification; the Forest Advisory Committee (“FAC”) for forest diversions, etc. [29]

The SPCBs issue “show cause notices” in the event of non-compliance by a company. The notice provides a period of generally 15-30 days in which the noticee has to explain why sanctions should not be imposed on them. [30] Sanctions may vary from cutting of electricity/water supply to criminal prosecution. The SPCBs have far-reaching powers to impose a stoppage of essential services such as electricity and water if a company is found to be operating in violation of the conditions mentioned in the Consent Order. The SPCBs can initiate prosecution before the courts. Moreover, Environmental Compensation amounts can also be imposed on the polluting industries. Moreover, if a unit is in serious non-compliance with environmental laws then the SPCBs may initiate proceedings before the NGT which may result in catastrophic conclusions for the company as NGT Act attracts penalty provisions that are much harsher as compared to other environmental laws.

Environment Permits

Although different states have different ways of analyzing the environmental impact of their companies, some common consent orders and environmental permits that a company must obtain from the SPCB is the Consent to Establish (CTE) order, as mentioned under the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974 and the Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981. Under these legislations, a company must submit their initial plans related to their manufacturing capacity, the pollution load, etc., to get the initial construction approval to start constructing the architecture of the building. Following CTE, the company must obtain a Consent to Operate (CTO) permit, which must be obtained by the company before they initiate any operations within the company. It is important to note that separate legislations have separate obligations and permits that need to be obtained by the companies. Another example can be the rules related to E-waste. The E-Waste Rules were introduced under the concept of “Extended Producer Responsibility – Authorization of Producers”, which required the company to have only one application with the CPCB. [31]

Some states have further expanded these compulsory rules further, wherein some have adopted the strategy of “auto-renewal” of consent orders/environmental permits, if a certain criterion is met by the company, based on their self-certification. This includes an analysis of the overall pollution load and production capacity of the company, the capital investment, etc.

Types of Liabilities Capable of Arising due to Breach of Environmental Laws or/and Permits, and Defenses Available

Penalty provisions are a core part of the various environmental laws in India. These provisions are triggered in the case of non-compliance or breach of statutory provisions such as non-obtaining of consent or environment orders. For instance, under the Water Act, a person who breaches the consent applicable is charged with a fine, along with an imprisonment of at least 18 months, which can be further extended to six years. Most likely all existing environmental laws will be amended (at some point) to be aligned with the NGT Act penalty provisions. [32] NGT act has stringent provisions in place in case of non-compliance of its order by an entity. Sanctions include imprisonment up to 3 years or a fine of INR 100 million or both. In case the company continues to operate in breach of the provisions then an additional fine applies up to INR 25,000 for each day the failure/contravention continues, after conviction for the first failure or contravention. From a conventional judiciary point of view, there have been past instances where the Supreme court or the High court have imposed exemplary damages in breach of such provisions. The prime example of it is the Sterlite’s Industries case of 2013 where the court imposed a fine of INR 1 billion, which was 10% of Profit before depreciation, interest, and taxes as it was found to be operating without a valid renewal of its environmental consent. [33]

E-Waste Legislation in India

As mentioned above, Electricity usage and E-Waste are the top reasons why a country takes drastic steps towards cryptocurrency mining aside from hidden political agenda. The concept of E-Waste is relatively new as it has recently come into focus, given the laser light speed at which technology evolves.

To cope with the increase in E-Waste, the central government just recently amended the E-Waste Management rules of 2016 in India. It facilitates and effectively implements the environmentally sound management of e-waste in India. It attempts to formalize the E-Waste recycling sector by routing E-Waste to government authorized recyclers. The E-Waste Management Rules have also incorporated a “self-declaration” mechanism, for example, the Reduction in the use of Hazardous Substances (“RoHS”) requirements.

The E-Waste legislation brings along with it, the collection targets for producers. The E-Waste collection target has been fixed at 70% of the waste generation quantity by 2023, where there is a yearly increase of 10%, starting from 2017-18. [34] Further, separate collection targets are introduced for new producers, who are beginning their sale operations.

To ensure compliance with the provisions, random sampling of electrical products in the market may be done by CPCB.

Conclusion

It is apparent from existing data that cryptocurrency mining is neither feasible nor legally accessible in India. The haziness of law and non-initiation by the Indian Government puts existing and potential miners in a state of dilemma. With a population of 1.3 billion and rising, it is crystal clear that India is in a prime position to take the lead on cryptocurrency on a global scale. However, the approach of the government has been rather skeptical. The ban on ASCI machines and the first implemented blanket ban on trading activities show the “burn the building to kill a fly” approach by the government.

However, the growth of cryptocurrency in India is still in its infancy. A progressive approach towards blockchain as a technology can result in India becoming the next superpower in cryptocurrency. Relief in FDI regulations and implementing subsidies in electricity costs for cryptocurrency miners will go a long way in ensuring that home producers remain competitive with the global players. Formally legalizing cryptocurrency mining will also ensure much stringent overwatch over illegal and fraudulent activities. In order to curb pollution and electricity usage, incentivizing miners to use sustainable energy such as Solar & Hydro will not only serve as an example to the entire world but will also ensure the longevity of the industry and better PR.

Blockchain has the potential to become the next Internet. Pundits at the beginning of the internet revolution criticized the technology and swore that it won’t last more than 5 years because it was “confusing and not useful for retail consumers” but here we are, 20 years later, reading an article on the next revolution on the Internet.

About the Authors

Rishabh Walia is currently a private legal consultant. He was previously an associate at Singhania & Partners LLP.

Muskaan Aggarwal is a 3rd Year Law Student at Jindal Global University and an Associate Editor at IJPIEL.

Preferred Method of Citation

Rishabh Walia and Muskaan Aggarwal, “The Future of Cryptocurrency Mining in India – Light or Dark” (IJPIEL, 11 September, 2021).

<https://ijpiel.com/index.php/2021/09/11/the-future-of-cryptocurrency-mining-in-india-light-or-dark/>

Editorial Team

Managing Editor: Naman Anand

Editors-in-Chief: Akanksha Goel & Aakaansha Arya

Senior Editor: Gaurang Mandavkar

Associate Editor: Muskaan Aggarwal

Junior Editor: Adarsh Kumar

Endnotes

[1] Tech Crunch, https://techcrunch.com/2018/03/12/john-oliver-helps-you-explain-cryptocurrencies-to-your-neighbor/, (last visited Sep. 4, 2021).

[2] Nathan Reiff, What’s the Environmental Impact of Cryptocurrency?, Investopedia (Sep. 4, 2021, 9:21 AM), https://www.investopedia.com/tech/whats-environmental-impact-cryptocurrency/.

[3] NFT is a unit of data which is stored on a digital ledger or blockchain, which indicates that a digital asset is unique and interchangeable in nature.

[4] Kerry Taylor-Smith, What are the Environmental Effects of Bitcoin and NFTs?, AZO Cleantech (Sep. 4, 2021, 10:29 AM), https://www.azocleantech.com/article.aspx?ArticleID=123.

[5] Id.

[6] Ryan Browne, Bitcoin’s wild ride renews worries about its massive carbon footprint, CNBC (Sep. 4, 2021, 11:08 AM), https://www.cnbc.com/2021/02/05/bitcoin-btc-surge-renews-worries-about-its-massive-carbon-footprint.html.

[7] Shubham Srivastav, Bitcoin mining in India: A profitable venture?, CNBC TV18 (Sep. 6, 2021, 02:30 AM), https://www.cnbctv18.com/cryptocurrency/bitcoin-mining-in-india-a-profitable-venture-9672401.htm.

[8] Andre Goncalves, What Is Bitcoin? Is Bitcoin Bad for the Environment?, Youmatter (Sep. 6, 2021, 02:35 AM), https://youmatter.world/en/bitcoin-bad-environment-impact/.

[9] Id.

[10] Rachel Lacey, Everything you need to know about eco-friendly cryptocurrencies, The Times (Sep. 6, 2021, 02:37 AM), https://www.thetimes.co.uk/money-mentor/article/eco-friendly-cryptocurrencies/.

[11] Id.

[12] Náñez Alonso SL et al, Cryptocurrency Mining from an Economic and Environmental Perspective. Analysis of the Most and Least Sustainable Countries, 14 Energies 14, 4254 (2021), https://doi.org/10.3390/en14144254.

[13] Environmental Performance Index, https://epi.yale.edu/epi-results/2020/component/epi (last visited Sep. 6, 2021).

[14] GlobalPetrolPrices, https://www.globalpetrolprices.com/electricity_prices/ (last visited Sep. 6, 2021).

[15] The World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EG.ELC.RNWX.ZS?end=2015&locations=IN&most_recent_value_desc=false&start=1971&view=chart (last visited Sep. 6, 2021).

[16] https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/~timo/diag/tempts_12monrunning_nh.png (last visited Sep. 6, 2021).

[17] William Suberg, BTC becomes legal tender in El Salvador: 5 things to watch in Bitcoin this week, Cointelegraph (Sep. 6, 2021, 02:57 AM), https://es.cointelegraph.com/news/bolivia-and-ecuador-among-countries-that-ban-cryptocurrency-trading-in-the-world.

[18] Bit2MeAcademy, https://academy.bit2me.com/en/legalidad-en-bitcoin/ (last visited Sep. 6, 2021).

[19] The World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/HD.HCI.OVRL?locations=IN (last visited Sep. 6, 2021).

[20] RBI Circular, https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/notification/PDFs/NOTI15465B741A10B0E45E896C62A9C83AB938F.PDF (last visited Sep. 6, 2021).

[21] Internet and Mobile Association of India v. Reserve Bank of India, MANU/SC/0264/2020.

[22] Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance, Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index, University of Cambridge (Sep. 6, 2021, 03:16 AM), https://cbeci.org/cbeci/comparisons.

[23] Vinamrata Chaturvedi, Is Bitcoin Mining Legal in India? Miners Still Don’t Know, CoinDesk (Sep. 6, 2021, 03:19 AM), https://www.coindesk.com/markets/2020/07/28/is-bitcoin-mining-legal-in-india-miners-still-dont-know/.

[24] Id.

[25] Mimansa Verma, Why cryptocurrency mining is a challenge in India, Quartz India (Sep. 6, 2021, 03:20 AM), https://qz.com/india/2030919/why-bitcoin-and-cryptocurrency-mining-is-challenging-in-india/.

[26] Id.

[27] Rajesh Mehta & Uddeshya Goel, India must democratise cryptocurrency; deals face FEMA compliance, investor identity, and other legal hurdles, Financial Express (Sep. 6, 2021, 03:23 AM), https://www.financialexpress.com/economy/india-must-democratise-cryptocurrency-deals-face-fema-compliance-investor-identity-and-other-legal-hurdles/2247691/.

[28] Id.

[29] ICLG, https://iclg.com/practice-areas/environment-and-climate-change-laws-and-regulations/india(last visited Sep. 6, 2021).

[30] Id.

[31] Id.

[32] THE WATER (PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF POLLUTION) ACT, 1974, Section 41, No. 6, Acts of Parliament, 1949 (India).

[33] Id.

[34] Rupali Sharma & Shahzar Hussain, India: E-Waste Management In India, Mondaq (Sep. 06, 2021, 3:30 AM), https://www.mondaq.com/india/waste-management/695996/e-waste-management-in-india.

Recent Comments