Abstract

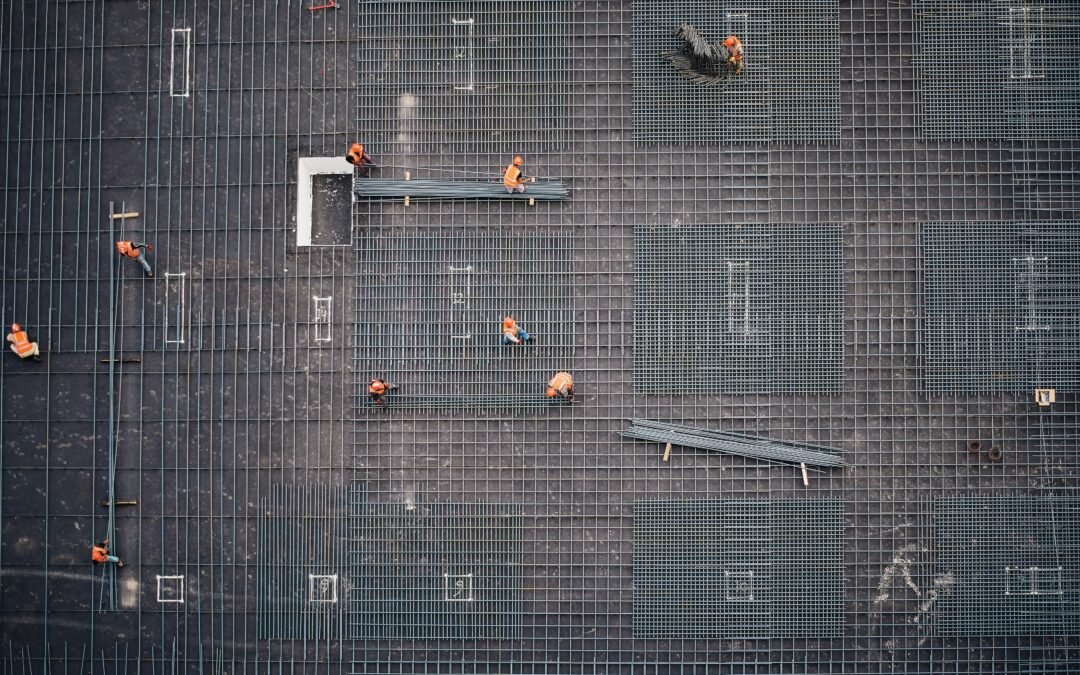

Infrastructural projects are in a boom phase in India, and when it comes to major infrastructure, construction, and energy projects, disputes are bound to arise. Disputes catering to infrastructure and construction projects are expensive, long, exceptionally complex, and puzzling. These disputes have in-depth technical facts and issues that take up an awful amount of time to conclude. With such large and complex disputes, arbitration has been the most viable and cost-effective way to provide timely conclusions. With high stake claims and damages, analysis of a large volume of documents, witnesses, and certain know-how of technical facts, construction arbitration has gained a lot of popularity in the recent past. With the paradigm shift in the resolution of disputes from litigation to arbitration in construction disputes, an issue has been persisting regarding their interrelationship. Through this article, the authors aim to analyze the attempt of the Legislature and the Judiciary to reach an equilibrium in this relationship.

Introduction

In the interest of increasing the ease of doing business, multiple diverse steps have been adopted in the Indian Economy. One of the facets that continue to remain of great importance in this exercise is adopting efficient and effective methods for dispute resolution, especially in high-stakes construction disputes. Working towards this aim, India has made multiple efforts to develop into an arbitration-friendly jurisdiction.

Since 2015, the law governing Construction Arbitration in India has seen a huge shift from a court-controlled to an arbitration-centric approach. Through the amendments following the Arbitration (Amendment) Act, 2015, the message of developing India into an Arbitration friendly jurisdiction has been reiterated by the Legislature. However, it is the Judiciary that plays a pivotal role in facilitating the growth of India’s Construction Arbitration regime.

Indian Judiciary, in complement to the approach of the legislature, laid down many landmark judgments that define the new and better course of Construction Arbitration in the Country. However, in multiple aspects, the law still remains a little ambiguous. Through this article, the authors are attempting to provide a balanced view on one such aspect i.e., exercise of Writ Jurisdiction of the High Courts. Further, the authors also attempt to assess the applicability of Writ Jurisdiction through the lens of Construction Arbitration.

Law Pertaining to Exercise of Writ Jurisdiction in Construction Contracts

At the outset, it can be observed that the Courts can be approached in three stages to exercise their writ jurisdiction in a construction contract dispute: (i) before invoking arbitration, (ii) during the course of arbitration, (iii) after the award has been delivered. This categorization is done for a better understanding of the approach of the Courts at various stages of arbitration.

(i) Before Invoking Arbitration

The first stage is where one of the parties to the arbitration agreement in the construction contract approaches the High Court, by either blatantly ignoring the existence of the arbitration agreement or by arguing that the dispute lies outside the purview of the agreement itself.

As per the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (hereinafter referred to as the Act), in such cases the courts will have to refer the parties to arbitration as – First, Section 8 of the Act explicitly restricts the power of the Courts for disputes pertaining to arbitration by providing that in case of an arbitration agreement, Courts shall refer the disputes to arbitration. Second, Clause (3) of Section 8 also provides that in case the Application made under Section 8 is still pending before the Court, arbitration can be initiated. This approach of the legislature expressly reflects that an attempt is made to restrict judicial interference to a bare minimum.

Further, in this regard, the Hon’ble Supreme Court through its judgment in the matter of reiterated the stance that Courts cannot be approached under a Writ Petition by ignoring the arbitration clause entered into by the consent of the parties involved. While referring the matter to arbitration and dismissing the writ petition, reliance is also placed upon the decision of the Hon’ble Supreme Court in the matter ofKerala State Electricity Board & Anr. v. Kurien E. Kalathil & Ors wherein this Hon’ble Supreme Court observed that:

“The contract between the parties is in the realm of private law. It is not a statutory contract. The disputes relating to the interpretation of the terms and conditions of such a contract could not have been agitated in a petition under Article 226 of the Constitution of India. That is a matter for adjudication by a civil court or in arbitration if provided for in the contract. Whether any amount is due and if so, how much and refusal of the appellant to pay it is justified or not, are not the matters which could have been agitated and decided in a writ petition. The contractor should have relegated to other remedies.”

In the light of this observation, it can be deduced that as contractual construction disputes largely deal with right in persona and not right in rem, thus, they should be referred to the mode of such dispute resolution as agreed by the parties. Rightly so, maintaining the sanctity of commercial contracts and enforcing themis essential for the maintenance of rule of law.

Therefore, it is safe to argue that the writ jurisdiction of the High Court cannot be exercised before invoking arbitration for issues arising out of construction disputes as it falls within the realm of private disputes that are to be settled as per the agreement within the contract. Thus, making it clear that a writ petition cannot be filed ignoring the rights of the other party as per the agreement to settle the dispute through arbitration.

(ii) During the course of arbitral proceedings

This stage arrives after the arbitration is initiated by either of the parties in the construction dispute or such matter has been referred to arbitration by the Court. For the sake of completeness, it is also important to mention that as per Section 21 of the Act, arbitration is commenced on the particular date when a request for the dispute to be referred to arbitration is received by the other party, generally, this is referred to as the notice of arbitration.

As stated above, from the bare perusal of the Act, it can be observed that the powers of Courts are restricted by the legislature. Section 5 read with Section 16 of the Act expressly provides that there can be no judicial interference except as provided in the Act and that the arbitration tribunal is competent to adjudicate upon its own jurisdiction. Thus, making it clear that Courts shall have only limited powers to interfere with the arbitration proceedings.

Further, the Hon’ble Supreme Court through its judgment inVidya Drolia has defined the ambit of such limited interference. This has been reiterated by the Court inDLF Developers. Through these judgments, the Hon’ble Apex Court laid down the scope of the Applications filed under Section 8 and Section 11 of the Act. As per the said judgments, the powers of the Courts under Section 8 and Section 11 are the same. Under both these provisions, the Court has to refer a matter to arbitration or appoint an arbitrator; the only exception to this is if, in a summary manner, the other side is able to prima facie establish the non-existence of the arbitration agreement. Further, whenever there is doubt, the Courts have to still refer the matter for arbitration.

Through the judgment laid down in the case ofVidya Drolia, the questions for determining the prima facie validity have been restricted to:

a. Whether the arbitration agreement was in writing?

or

b. Whether the arbitration agreement was contained in an exchange of letters, telecommunication, etc.?

c. Whether the core contractual ingredients qua the arbitration agreement were fulfilled?

d. On rare occasions, whether the subject matter of the dispute is arbitrable?

Therefore, the authors believe that it is safe to conclude that under the Act, the power of the Court is restricted to just determining the existence of arbitration agreement.

Recourses available under the Act

It is safe to argue that once the arbitration is initiated, the relief that is provided by the Act is holistic in nature. Section 9, read along with Section 17 of the Act, provides for recourse to seek interim relief in case of urgency from the Court as well as from the Tribunal, respectively. Thus, it reduces the chances of interfering with the procedure under the Act through the Writ Jurisdiction of the Court. Section 9(3) of the Act states that an application under section 9 will not be entertained by the court unless the court finds that the remedy sought from an arbitral tribunal would be ‘inefficacious’ under section 17. This substantiates that the arbitrator is given first preference to provide an interim relief which further harpers on the fact that through the Act, a clear attempt has been made to bestow upon the arbitral tribunal, all the powers necessary to resolve the dispute, so that interference with the court is limited.

However, the next question that arises is that at such a stage, can court interfere through the Writ Jurisdiction available under Articles 226 and 227 of the Constitution.

There is no doubt that the powers of the Court are vast enough to exercise their writ jurisdiction over the arbitration proceedings; however, through the recent decisions, it can be observed that Courts have exercised restraint in interfering with the proceedings under writ jurisdiction.

Through the series of decisions laid down by the Apex Courts, it can be observed that Judiciary has at every step attempted to uphold the intentions of the legislature as reflected within the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996.

In the case ofU.P. Power Transmission Corporation Limited v. CG Power, the question pertaining to the powers of the Court under the writ jurisdiction was raised before the Hon’ble Court. While deciding upon the contractual dispute, the Hon’ble Supreme Court observed that the existence of an arbitration clause does not exclude the jurisdiction of the High Court under Article 226 of the Constitution. However, such interference has been further clarified by the succeeding judgments of the Apex Court. In the case ofBhaven Construction v. Executive Engineer Sardar Sarovar Narmada Nigam Ltd., the court laid down the “exception rarity” test wherein Court has laid down that writ jurisdiction can only be analyzed when either of the party is left remediless under the statute or a clear ‘bad faith’ is shown by one of the parties. This reflects upon the fact that an exceptionally high threshold has been laid down to exercise writ jurisdiction in cases involving an element of arbitration.

(iii) After the award has been delivered by the Tribunal

As per the nature of proceedings, the arbitrator/s delivers the arbitral award on the issues raised before the Arbitral Tribunal. The Arbitral Award becomes executable after 3 months if it is not challenged by the parties involved in the arbitration. Further, Section 37 of the Act also provides provisions to appeal in case an impugned party wants to challenge the orders/award passed as per the provisions of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996.

With regards to arbitration,the position of law is crystal clear, the Act provides for an alternate efficacious remedy which in itself defeats the objective of approaching the court under Article 226 and 227 of the Constitution of India.

Separately, it is pertinent to also mention that if the award passed as per the Act keeps getting challenged under the writ jurisdiction, the purpose of approaching the tribunal under arbitration will fail. Keeping this in consideration, as explained above, various High Courts and Hon’ble Apex Court has restricted their approach while interfering with the decisions of the arbitral tribunal.

Exception

As we have discussed, courts are adamant in preserving the sanctity of arbitration by not interfering in the dispute resolution process at either stage of the arbitration. However, there are a few exceptions that have been laid down by the court through some key cases.

InAshish Gupta v. IBP CO. Ltd., Delhi HC held that the non- obstante clause in section 5 is purely discretionary and not mandatory or obligatory. Despite an alternative remedy, the high court may invoke Writ Jurisdiction under Article 226 of the Constitution of India if: –

- There is a violation or failure to enforce fundamental rights.

- There is a violation of the principle of natural justice.

- There is no jurisdiction issue related to an arbitral tribunal.

The courts have also emphasized that the Court can exercise writ jurisdiction in case there are legitimate reasons to do so, but these circumstances should be extraordinary.

InSREI Infrastructure Finance Ltd. v. Tuff Drilling Pvt. Ltd., the court held that tribunals must follow the principles of natural justice. The tribunal cannot ignore these principles and pass a judgment in favour of a party to the dispute biasedly and arbitrarily. It is also pertinent to note that High courts have overriding power over arbitral tribunals in the country as per Article 227 of the Constitution of India.

In Punjab State Power Corporation v. EMTA Coal Ltd., the Supreme Court stated that courts can exercise their writ jurisdiction if the order passed by the arbitral tribunal lacks the jurisdiction or is grossly irrational and arbitrary. In the case ofRapid Metrorail Gurgaon Limited v. Haryana Mass Rapid Transport Corporation Limited and Ors, it was held that high courts can exercise their writ jurisdiction in cases where an issue of public interest is involved and an order by the arbitral tribunal would be unfair to the public and the parties involved. In another case ofUnitech Pvt. Ltd. and Ors. v. Telangana State Industrial Infrastructure Corporation (TSIIC) and Ors. Supreme Court also stated that the courts can exercise their writ jurisdiction powers if ‘recourse to a public law remedy can be invoked’ justifiably. Through these decisions, it is safe to conclude that writ jurisdiction can be exercised to ensure rule of law and serve public interests.

In the case ofRam Barai Singh & Co. v. State of Bihar and Ors., the Supreme Court held that courts can apply their discretionary power for either exercising their writ jurisdiction or relegating to availing alternative remedy.

In the case of‘Deep Industries’, the Supreme Court introduced the ‘Patently Lacking in Inherent Jurisdiction Test’ and held that courts should refrain from interfering with orders of tribunals which are patently lacking the jurisdiction to entertain the case. However, in this judgment, the court did not elaborate what would amount to lacking in inherent jurisdiction, which was clarified further in the case ofPunjab State Power v. Emta Coal Limited, wherein the arbitrator’s order under Section 16 of the Act was challenged under Article 227 of the Constitution. The court stated that a patent lack of jurisdiction is when perversity is found on the face of, i.e., unreasonable and lacking the proper jurisdiction to entertain the case.

Analysis and Conclusion

The situation regarding exercising writ jurisdiction still seems to be unclear. While courts have stated that the alternative remedy of dispute resolution in the form of arbitration should be preserved, courts have also asserted the fact that arbitration cannot oust the jurisdiction of the Courts. The High Courts and the Supreme Court can exercise their writ jurisdiction whenever deemed necessary; however, this is restricted to exceptional cases only, as has been previously discussed.

The authors believe that the courts are striving to achieve a balance between exercising their writ jurisdiction powers to ensure that there is no denial of justice while also upholding the sanctity of contract by keeping in consideration the value of the contractual arbitration and minimal judicial interference. This approach of the judiciary is highly laudable and is a stepping stone towards building an arbitration-friendly jurisdiction.

Further, if looked closely in the case of construction disputes, as discussed earlier, the nature of disputes is complex, and it takes an arduous amount of time to resolve them. The claims in these cases can start anywhere from 20- 30 crore to hundreds of crores depending upon contractual violations and the damages claimed thereunder. In such cases, the merits of the matter are heavily technical and substantially specific to the contract as agreed between the parties. Therefore, in such construction arbitral arrangements, the ambit of writ jurisdictions should be even restrictive as it involves discussions on facts, appreciation of evidence, and technical know-how of the agreement. In rare circumstances, as laid down in Bhaven Construction, the disputes involve an element of rights in rem that require judicial consideration. It is pertinent to keep this in mind while approaching the Court to exercise writ jurisdiction in case of a dispute arising out of a construction contract.

About the Authors

Ms. Shatakshi Tripathi is an Advocate at the High Court of Delhi.

Kshitij Pandey is a 3rd Year Law Student from Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University (RMLNLU) from Lucknow, and an Associate Editor at IJPIEL.

Editorial Team

Managing Editor: Naman Anand

Editors-in-Chief: Jhalak Srivastav and Akanksha Goel

Senior Editor: Hamna Viriyam

Associate Editor: Kshitij Pandey

Junior Editor: Harshita Tyagi

Preferred Method of Citation

Shatakshi Tripathi and Kshitij Pandey, “Writ Jurisdiction of the High Court in the case of Construction Arbitration” (IJPIEL, 25 March 2022)

<https://ijpiel.com/index.php/2022/03/25/writ-jurisdiction-of-the-high-court-in-the-case-of-construction-arbitration/>

Recent Comments