Abstract

With the world changing its stance from non-renewable energy to renewable energy in its efforts to counter climate change, it has become imperative for nations to experiment with the legal regimes that are in place, specifically those developing nations that seek foreign investment. Consequently, investment arbitration has entered the picture. Investment arbitration as a mechanism for addressing disputes in the energy sector is an ever-growing trend. Since the setting up of the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) Convention in 1966, foreign investors have been dragging states to this arbitration institution in order to seek appropriate arbitral awards. However, India’s position, notwithstanding its promises of clean energy and energy transition, remains interesting.

Through this blog post, the authors analyse the concept of investment arbitration in India’s energy sector. They begin by discussing arbitration and the energy sector, before delving into the concept of investment arbitration in India, its past as well as present, while laying particular emphasis on the Indian Budget for the F.Y. 2022-23. Towards the end, the authors explore the future possibilities of investment arbitration while providing their concluding remarks.

Article

“We need to diversify our economy, and the energy industry would be a great place to begin that diversification”

-Sharron Angle

As the world changes, so do the needs of humankind. Since time immemorial, these needs have been driven by the decisions of people in power. Even in contemporary times, we must look towards the policies and legislations made by high-level authorities; policies and legislations that are implemented for the betterment of citizens residing in their respective territories.

In recent years, the world has had to strive hard to fight one of the biggest global threats we’re facing – the phenomenon of climate change. Governments at both, the national and international levels, have formulated a broad array of measures as well as conventions in efforts to counter it. This growing menace has brought the world to its knees and made it essential to adopt sustainable measures to protect the environment. Not only has India followed the lead, but it has also emerged as one of the pioneers in this struggle against climate change. In order to do so, it took heed of the aforementioned quote by Ms. Sharron Angle and started its experimentations in the energy sector.

At the domestic level, India established its very own Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) to reduce the country’s reliance on fossil fuel-based consumption, that is, non-renewable energy, and shift to the renewable energy sector. Subsequently, it established the Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI) and the Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency (IREDA). Furthermore, India’s budget for the F.Y. 2021-22 and F.Y. 2022-23 aimed at keeping India’s promise to achieve a target of 227 GW by the end of 2022, and 450 GW by 2030. This move led to the development of the Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme, along with the provision of subsidies, interest-free loans, and additional capital infusion, all contributing to the betterment of the sector. The PM Gati Shakti Plan was another significant initiative introduced by the Indian Government. In addition, the budget for the F.Y. 2022-23 brought about a rise in the capital expenditure by 35.4% (amounting to INR 7.50 crore) to induce more private party investment, due to its vehementemphasis on energy transition and clean energy mission.

At the international level as well, India has taken steps showing its willingness to switch to the renewable energy sector. In 2015, it launched theInternational Solar Alliance (ISA) with France at the 21st Conference of Parties (COP21) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Further, at COP 26, held in Glasgow from 31st October to 13th November 2021, India put forth ambitious targets for countering climate change. It further made mammoth claims about its energy transition mechanisms, andpolicies to facilitate the same. As already mentioned, India had set a target of achieving 450 GW of renewable energy production by 2030. Ambitious as it sounds, it must not be forgotten that India is the only country to fulfil its Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) with respect to climate change, and it has also shown its full support to the Paris Climate Agreement. The actions mentioned above are not random shots in the air. Rather, they are initiatives that showcase the way India’s energy sector, along with its allied sectors, is on the rise.

Before coming to the aspect of investment arbitration in India, let us first understand the need for arbitration in its energy sector.

When bringing about the LPG (Liberalization, Privatization, and Globalization) reforms in 1991, the Government of India noticed that the State Electricity Boards (SEBs) were slowly becoming inefficient and generating huge losses. Treated as mere political instruments for those in power, they were failing to fulfil their primary function – being generation, transmission, and distribution entities. Consequently, the Government remoulded the SEBs to the modern-day Distribution Companies (DISCOMs). The Government was rather optimistic about the formation of DISCOMs, being of the view that, in the wake of this remoulding process, these entities would emerge successful after years of losses. It was expected that this would turn the tide of inefficiency, and help thembecome financially stable profitable entities, since then private players were allowed to play ball in the energy sector too, vide the Electricity Act of 2003.

However, the tide did not turn as expected, and DISCOMs continued to suffer losses instead of turning into profitable entities. According to a report by the Power Finance Corporation, the aggregate loss of DISCOMs was approximately INR 900 billion. It was even claimed that these DISCOMs had accumulated dues amounting to INR 87,000 crores by March 2020, making it abundantly clear that they would be unable to repay the electricity generation companies. This opened the gates to an array of legal complications, right from the project commissioning differences, to delays in payments, bankruptcies, etc.

Usually, when such disputes arrive, the Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (CERC) takes it upon itself to them. However, since the option to appeal is readily available to the party against whom the judgment is passed, these judgments are often challenged in Appellate Tribunals, and ultimately, before the Hon’ble Supreme Court of India. This has burdened the alreadyoverburdened judiciary with cases related to energy sector disputes and as a result, the prolonged court battles have continued, leading to the bleeding of investors’ time and money.

Faced with this issue, private investors started exploring alternative options to seek justice, and hereby, the mechanism of institutional arbitration came into the picture. This mechanism has since been proactively utilised by the energy sector. The major benefit of institutional arbitration is the proficiency of the individuals who deliver the arbitral awards in a case, i.e., experts in the sector who are appointed to resolve the disputes. Not only does this serve to establish trust in the minds of investors, developers, and institutions about the comprehension of the nuances and intricacies of the case, but it also paves the way for a speedy resolution of disputes. Vide the 2019 Amendment to the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, “fast track procedures” for international commercial arbitration have been given great importance under Section 29B, which proves to be a lucrative option for international investors. The Amendment also takes care of domestic commercial arbitration mechanisms under Section 29A, which imposes a time limit for the Arbitral Tribunal to give its final award.

To ensure that the final arbitral award is the best possible version of itself, there exists a process of “scrutiny of the award” which takes place before the final order is passed. This scrutiny is done by the subject experts who oversee the arbitral proceedings between the parties in conflict. Furthermore, Section 34 of the said Act provides for scope of challenging the arbitral award, if certain conditions are met. In addition, the Indian Government, to give a boost to institutional arbitration and Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs), has enabled the energy sector to incorporate “an institutional arbitration clause” with atimeline nearing up to three months. All the aforesaid factors have encouraged investors, developers, and even large corporations in the energy sector to opt for arbitration as a dispute resolution mechanism instead of lining up in courts.

Now, it is pertinent to ascertain, or rather, question as to why such measures are being taken by the Indian government, as well as to why the arbitration sector is witnessing a spike in India, specifically in the energy sector.

The energy sector is one of the sectors in India which allows for 100% Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). In addition, the mammoth pledge made by India in COP 26 circumnavigated around energy transition and clean energy. The target of achieving 450 GW of renewable energy capacity would not be possible if private entities were prevented from entering the playing field. In fact, their entry becomes pivotal because the achievement of the humungous target of 450 GW renewable energy seems to require roughly $533 billion. It must be noted that the aforesaid figure is just for the renewable energy sector; the total investment required for the energy sector as a whole, is around$1 trillion. These investments would consecutively facilitate the creation of sustainable and suitable infrastructure, thereby boosting the businesses involved in the energy sector. At the same time, it would also utilise and develop human resources in the respective areas.

When such huge investments would flow in on both, the domestic as well as international fronts, disputes would arise as well. Investors, rather than going for the conventional mode of seeking justice in courts, would prefer to opt for the modern-day “outside of court settlements”, i.e., arbitration, which is known asInvestment arbitration. It refers to the procedure established to resolve dispute(s) between foreign investors and the host countries in which they have invested. Also called Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS), these investment arbitration proceedings are usually consented to by the host states in International Investment Agreements (IIAs), Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs), Free Trade Agreements (FTAs), or at multilateral levels by being a party to The Energy Charter Treaty (ECT).

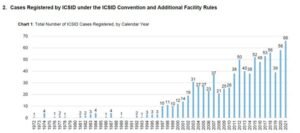

Source: International Arbitration Information by Aceris Law LLC

As we can see from the above chart, the time period from 1972 to 1996 witnessed a fairly low registration of cases with respect to investment arbitration. However, moving towards the end of the 20th century, i.e., 1997 onwards, we see a spike in cases of investment arbitration. This could be due to the opening up of various economies of the world, as well the IIAs, BITs, FTAs, and ECT showing the world the benefits of arbitration. At the onset of the 21st century, i.e., the period from 2000 to 2020, we see a boom in the number of cases with respect to investment arbitration. Now, the above-mentioned data speaks only of cases at the international level. The picture in India is completely different.

It won’t be out of place to mention that investment arbitration in India has evolved with time. The 5 stages of investment arbitration, in order, are – scepticism, openness, increased participation, protectionism, and lastly, a state-centric approach towards BITs. After the LPG policy of 1991, India became an excellent destination for investment by foreign investors. Although the stance of the government fluctuated from time to time, the investments poured in. And along with the investments came disputes related to investment arbitration. As per thedata available in Investment Policy Hub, UNCTAD, there were twenty-six cases wherein India has appeared as a Respondent State, and nine wherein it appeared as the Home State of the Claimant. Even though all cases have their own standing, the two prominent ones include Vodafone v. India and Cairn v. India, both of which were filed following the announcement of a retrospective taxation system for corporate entities.

Looking at the history of investment arbitration in India, we are presented with a rather rough picture. India’s relationship with BITs started when it signed its first-ever BIT with the United Kingdom in 1994. Despite the fact that the culture of BITs has started in India, the nation is not a party to the ICSID Convention till date. During this time, the world witnessed the openness shown by the Indian Government towards the concept of investment arbitration. However, this openness soon turned into something diametrically opposite when the Dabhol Power Plant project dispute arose. In addition to raising questions about the efficiency of the Indian Judiciary, this dispute forced India to switch to a ‘protectionist’ approach. One thing led to another, and the Indian government began cancelling telecom licenses, which gave birth to a new set of issues.

However, the government changed in 2014, and the new government’s approach towards the arbitrational regime caught the international community’s attention. The NDA-led government took two major steps in this regard, the first one being the establishment of a model BIT structure, and the second one being the abolishment of the FDI approval process. The power was delegated to the ministries for their own FDI requirements as they deemed fit.

Now, when we look at the modern-day scenario, we find that India is still sitting on a fence about the concept of investment arbitration. In addition to a fair share of contribution being made to bring about change in the investment arbitration sector, India has also signed three BITs in three consecutive years with Belarus, Kyrgyzstan, and Brazil, respectively. While the first two BITs opened the gates for theinvestors having recourse to investment arbitration, the BIT signed with Brazil has been considered to be a significant step in the Indian arbitral mechanism. This BIT has taken initiated the shift from the conventional Investor-State arbitration mechanism to a State-State arbitration mechanism, which implies that the claims commission and diplomatic protection would co-exist as a part of this BIT.

However, the picture is not as rosy as it may seem. There exist two major lacunas in the Indian arbitration mechanism that are akin to thorns of a rose. The first is enforcement issues that arose when India issued a “commercial reservation” while being party to the New York convention. It essentially means that the provisions related to Article 53(1) of the ICSID Convention are not applicable in India. It reads as:

“The award shall be binding on the parties and shall not be subject to any appeal or to any other remedy except those provided for in this Convention. Each party shall abide by and comply with the terms of the award except to the extent that enforcement shall have been stayed pursuant to the relevant provisions of this Convention.”

The notion of “commercial reservation” was brought up by the Hon’ble Delhi High Court in two cases, namely, Union of India v. Khaitan Holdings (Mauritius) Ltd & Ors (2019) and Union of India v. Vodafone Group PLC United Kingdom & Anr. (2017).

The Hon’ble Court specifically stated that, since investment arbitration escapes commercial nature, none of the provisions of the New York Convention would be applicable to such cases.

The second reason so as to why the investment arbitration mechanism irks the investors is the jurisdiction of the Indian Arbitration and Conciliation Act of 1996. Under the said Act, the concept of investment arbitration is neither composed of international commercial arbitration nor domestic arbitration, thereby kicking the aspect of investment arbitration, out of its jurisdiction entirely. Though this could be considered as a lacuna in Legislation, many consider this to be a move by the Government to escape the liability of paying hefty amounts to the foreign investors as an arbitral award.

Coming to the future aspects of investment arbitration in India, there can be no denial of the fact that there is a need for a better mechanism than the one in the present scenario. It could be argued that the present mechanism would push the notion of investment arbitration into the darkness; India’s unwillingness to ratify the ICSID Convention could be said to speak volumes in itself. Furthermore, the future looks bleak as the new BIT with Brazil has completely evaporated the concept of investment arbitration, as a result of which, possibly no arbitral awards can be bestowed and enforced in India. This not only shows the state-centric approach being followed by India but also scares off foreign investors who plan on investing in India. India needs to settle on a concrete position with respect to investment arbitration in front of the international community because presently, there is a clear disparity between India and the discussions taking place in the UNICTRAL Working Group III. While the latter proposes the incorporation of an Appellate mechanism for resolution of disputes, or the formation of a new standing body called the ‘Multilateral Investment Court’, India is looking towards the establishment of ‘specialist courts’ for dealing with disputes related to investor claims and compensation. This move could prove to be a double-edged sword for India; on the one side, it would establish a body dedicated solely to this subject area, but on the flip side, it might end up isolating India completely from the aspect of investment arbitration.

Conclusion

Looking at the current Indian scenario, it is clear that the sector of investment arbitration is still at its infancy stage. This is not because the idea of investment arbitration is completely new – rather, it is due to the protectionist regime imposed by the Indian government. The energy sector is ever-expanding, especially with the onset of the measures and policies being undertaken to tackle the devil of climate change. Although India has its share to boast about, such as its measures to induce foreign investors into investing in the renewable energy sector, its legal system is yet to be enhanced and modified by taking cognizance of the protection sought by the foreign investors.

In addition to the ‘clean energy mission’ and ‘energy transition’, India must understand that the aspect of green hydrogen and nuclear energy also needs to be taken into consideration. The fact that Green Hydrogen is a sector that the government is willing to explore has been proven by the rolling out of theGreen Hydrogen Policy in February 2022. This policy amalgamates India’s promise to the international community with the needs of the country. Furthermore, nuclear energy remains an unexplored area by private players due to the Indian government’s scepticism regarding them. Hence, nuclear energy is still the domain of the Department of Atomic Energy (DAE), which is headed by the Prime Minister of India.

In conclusion, India’s tryst with investment arbitration in the energy sector has a long way to go. Not only is there is a need for proper domestic legislation for the protection of foreign investors, but for the domestic market as well. It is safe to say that this tryst needs a lot of attention and care.

About the Authors

Mr. Yazad Udwadia is an Advocate practicing Litigation and Dispute Resolution in Mumbai and is also pursuing a Post Graduate Diploma in Business Management, PGDBM (2022).

Abeer Tiwari is a 3rd-year Law Student from Balaji Law College, Pune. He is also an Associate Editor at IJPIEL.

Editorial Team

Managing Editor: Naman Anand

Editors-in-Chief: Jhalak Srivastav and Akanksha Goel

Senior Editor: Muskaan Singh

Associate Editor: Abeer Tiwari

Junior Editor: Ria Goyal

Preferred Method of Citation

Yazad Udwadia and Abeer Tiwari, “India’s Tryst with Energy Investment Arbitration and the Contemporary World” (IJPIEL, 4 April 2022)

<https://ijpiel.com/index.php/2022/04/04/indias-tryst-with-energy-investment-arbitration-and-the-contemporary-world/>

Recent Comments