Abstract

The international investment arbitration community, more specifically the EU investors, is facing a tough time due to the overstretched primacy of the European Union (“EU”) law. The Energy Charter Treaty (hereinafter referred to as “ECT”) was signed in the year 1996 to promote long-term cooperation in the energy sector based on mutual benefits. But with the recent set of rulings by the European Court of Justice (“ECJ”) examining the applicable law along with the admissibility of investor-state arbitration claims has forced EU investors to look for “alternative” routes to pursue intra-EU investor claims.

Through this blog post, the authors intend to cover the aspect of investor-state arbitration under the ECT with a focus on intra-EU investor-state claims. In this research, the authors aim to first introduce the concept briefly, followed by a discussion elaborating on the latest jurisprudence on the settlement of energy disputes in the EU and the challenges surrounding such developments. The authors have focused on the three landmark judgments about the issue for addressing potential challenges that the investment arbitration industry is likely to face. The article is concluded with a remark on the ongoing developments and the implications the current practices can have on the EU-investors.

Introduction

The ECT came into existence post the cold war era, which resulted in significant changes affecting European and world politics concerningunparalleled interest in Energy cooperation between the West and the former Soviet Union. The objective behind signing the charter was to promote the flow of private investment by encouraging the participation of private investors and ensuring respect for state sovereignty over natural resources. Further, an environmentally sound energy policy required a binding internationallegal framework which would extend protection to the four pillars, i.e., trade, transit, energy efficiency and investment. Before dwelling on the aspect of dispute resolution, let us develop a brief understanding of ECT and energy disputes. As mentioned above, energy has been one of those sectors where the projects undertaken areusually complex, and require enormous capital for the smooth functioning of the project. Owing to such nature, the energy sector often proves to be a breeding ground for disputes. Moreover, the ECT is seen to be the most used treaty in the area of investor-state arbitration, with as high as135 claims filed as of 2021. It could be explained by the following statistics by theInternational Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) in their Annual Report for the FY 2021:

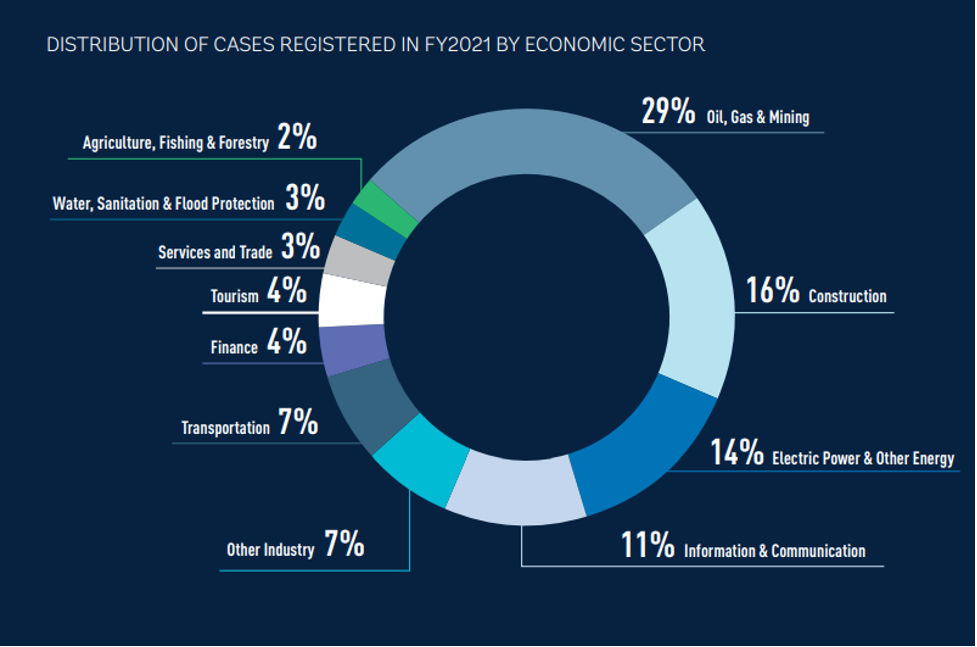

Source:Annual Report on the operation of the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes 2021

As depicted in the above chart, the cases registered for ICSID proceedings comprise of Oil, Gas, and Mining sectors for the largest portion of cases (29%), which is followed by the Electric Power and Other Energy sectors (14%). Analysing the Annual Report (2021), as presented by ICSID,shows that 8% of the cases were instituted based on ECT, which equates to a total of six cases concerning ECT under ICSID.

Category of Energy Disputes

Moving on, let us now look at the variety ofcompanies involved in energy projects, carefully bifurcated into three parts of the supply chain, namely- upstream, midstream, and downstream. Additionally, these segments of the energy sector represent the four main activities of the energy sector- exploration, production, refining & distribution and selling. These are the major sectors where disputes arise. These disputes are classified majorly into three categories, where arbitration can be used as an instrument of dispute settlement:

1. State-to-State Disputes: As the title suggests, under the said category of disputes, two separate states that are party to a bilateral or multilateral treaty are involved. Even if we take into cognizance the energy sector, the state-to-state dispute settlement goes way back before the investor-state arbitration. These disputes were usually resolved through court litigation, diplomatic channels, and ad-hoc tribunals.The aspect of state-to-state dispute settlement generally finds its base in the previous Friendship, Commerce, and Navigation (“FCN”) Treaties and certain investment treaties. An example of ‘exclusive state-to-state arbitration’ could be traced back to theBilateral Investment Treaty (“BIT”) signed by Germany and Liberia in the year 1961. However, it is to be noted that this form of dispute settlement lacked the touch of institutional arbitration, i.e., cases being taken up by ICSID, or ICC for that matter.

2. Investor-State Disputes: The energy sector across the world has shown the trend of state monopoly, specifically in the sector of extraction and supply of energy. However, with the onset of the inflow of foreign investment in the energy sector, the nature of the disputes from state-to-state disputes has changed from investor-state disputes. In 1969 the aspect of investor-state dispute was incorporated in theBilateral Investment Treaty between Italy and Chad. Besides, it was in the landmark case ofAsian Agricultural Products Limited v. Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka (ICSID Case No. ARB/87/3) where for thefirst time, thearbitral tribunal exercised its jurisdiction under the clause for investor-dispute dispute settlement. This category is further bifurcated into two categories: treaty-based disputes, and contract-based disputes.

3. Private Disputes: As the name suggests, these kinds of disputes arise when the private companies involved in the energy sector engage in disputes arising out of a wide range of issues. These disputes, if arbitrable, usually fall under the category of commercial arbitration or international commercial arbitration.

Settlement of Energy Disputes in EU

The Bilateral and multilateral investment treaties such as the ECT are in place to accord protection to the fossil fuel industry from the impacts of changes to a host State’s regulatory framework. It is essential to note that despite being self-sufficient in the energy domain, theEU imports the majority of its oil and gas supply. Concerning the investment protection mentioned above, the ECT can be categorized into the following- an intra-EU multilateral treaty amongst the 27 EU Member States [1]; an extra-EU MIT between 27 EU Member States and 28 non-EU states [2]; and MIT wholly external to the EU Member States among 28 non-EU ECT Member States [3]. More importantly, EU Member States are themselves contracting parties to the ECT, providing them with investment protection obligations under the treaty. All members of the ECT are thus internationally responsible for fulfilling the obligations set forth in the treaty. In an event that either contracting party to the treaty fails to fulfil its obligations, a claim can be brought before the courts/ administrative tribunals or through international arbitration- ad hoc or institutional. Over the years, investment arbitration has been the preferred route for dispute settlement under the ECT, although it is interesting to note that recent CJEU (Court of Justice of the European Union, hereinafter referred to as “CJEU”) decisions have put several sticks in the wheels of investment arbitration proceedings concerning intra-EU ISDS claims. While it is debated that these rulings of the CJEU do not dismiss the pending ISDS claims or pose any threat to any future claims, it does put a halt on the recognition and enforcement of intra-EU investment arbitration awards. Let us look at the three disruptive landmark judgements that could possibly change the landscape of investor-state arbitration in the EU.

ACHMEA RULING ON APPLICABLE LAW

In the year 2018, the CJEU laid down jurisprudence regarding the incompatibility of the arbitration clauses within intra-EU BITs with EU law. InSlovak Republic v. Achmea BV, the CJEU held that the arbitration clause contained inArticle 8 of the 1991 Netherlands – Slovakia BIT (the “BIT”) adversely affected the autonomy of EU law and was thus incompatible. The CJEU was of the view that the arbitration clause contained in the BIT removes disputes which involved interpretation/application of EU law from judicial review provided by the EU legal framework. It further stated that EU law is an independent source of law- the EU treaties hold primacy over the individual law of EU Member States, justifying that these characteristics “have given rise to a structured network of principles, rules and mutually interdependent legal relations binding the EU…”. Further, the CJEU described it as the “keystone” of the judicial system laid by the EU treaties, which intends to maintain consistency and uniformity in the interpretation and application of EU law as embodied inArticle 267 TFEU (Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union). At the time when this judgement was declared, the CJEU had not overtly taken a position on multi-lateral treaties but had decided that the ISDS provisions contained in intra-EU BITs are incompatible with EU law as theyundermine the power of the EU courts.

KOMSTROY IS THE LAW

This decision was followed by theKomstroy judgement, where the CJEU went ahead and offered clarification for the reasoning that it applied in the Achmea case stating that the former ruling applies to all intra-EU disputes under the ECT regardless of their multilateral character or the fact that it also concerns non-EU countries. The CJEU explicitly held that the ISDS provisions under the ECT“must be interpreted as not applicable to disputes between a Member State and an investor from another Member State concerning an investment made by the latter in the first Member State”. The CJEU stated that such interpretation must be uniform for the reason that the autonomy of the EU legal order and EU law calls for a consistent interpretation, if ISDS mechanisms are allowed instead of adjudication by national courts, the above-mentioned consistency cannot be ensured as arbitrators are not bound to apply EU law.

This decision of the CJEU and the reasoning provided for it has been widely criticized for not taking into consideration international law and rules on treaty interpretation and also for not addressing the substantial body of case law under the ECT on the interpretationof Article 26 of ECT. With theKomstroy decision, the CJEU demarked the limits within which the international investment tribunals are legally allowed to operate under EU law. Further, displayed that there is no place for intra-EU arbitration proceedings under the Energy Charter Treaty. In other words, the interpretation offered by the ECJ is such that the dispute settlement mechanism inArticle 26(2)(c) of ECT does not apply to the disputes between a member state and an investor of another member state relating to an investment made by the latter.

Practitioners criticized the decision as scant and inconsistent reasoning likely to be based on politicalconsiderations as opposed to a reasoned interpretation of the law which could eventually undermine investor confidence in the EU judicial system. It also creates uncertainty regarding the possible protection of investors within the EU forenergy investments because of the threat that the Member States would not abide by the ECT. Originally, the arbitral tribunal appointed to hear claims under the ECT derived its competence from Article 26 of the ECT, but with theKomstroy ruling in existence, this tribunal lacks jurisdiction. Despite the landmark ruling, there is still uncertainty as to whether arbitral tribunals will exercise jurisdiction over intra-EU ECT claims or refuse the same. Subsequently, on October 26, 2021, adecision by the Grand Chamber of CJEUPL Holdings confirmed the fact that arbitral tribunals are now at constant risk of facing jurisdictional challenges.The court held that based on EU law, the Member States are “obliged” to question the validity of arbitration agreements in Intra EU investment disputes, along with the jurisdiction of the tribunal as well as the enforceability of the award. The decision of the PL Holdings case points toward an arbitration practice which would not only be more expensive and lengthier but could also lead to more risky procedures. Effects of this decision had already started to roll out when a Lithuanianinvestor dropped its claim against Denmark for a dispute based on intra-EU BIT because of Achmea’s decision.

SPAIN’S WIN ON INTRA-EU OBJECTION

Recently for the first time, an investment tribunal has held a member state’s intra-EU objectionhanding Spain a landmark jurisdictional win against an ECT claim it had faced. This cannot be the first time an EU member state invokedAchmea to challenge the tribunal’s jurisdiction, as it has become a frequent political shift in matters concerning Intra-EU investment resultantly.

It was a radical development for the investment arbitration industry and a landmark win for Spain as a Stockholm-seated tribunal was the first to dismiss an intra-EU investment arbitration claim on jurisdictional grounds. The tribunal upheld Spain’s argument that EU law trumped the ECT in the dispute by reinstating the relevance of ECJ’s jurisprudence. The arbitration claim against Spain was filed by two Danish renewable energy investors over Spain’s pushback of regulatory policies designed to encourage investment in this sector.

The decision of the tribunal confirmed that the Achmea judgment applied to ECT disputes, putting to rest the doubts and concerns surrounding the applicability of ECJ’sKomstroy ruling. The dispute concerned one of over 50 investment treaty claims Spain has faced from renewable energy investors over its regulatory changes followed by the 2008 global financial crisis.Green Power and SCE had filed their claim in 2016, seeking around €74 million in damages. The hearing commenced in Stockholm in 2019, whereinthe proceeding was bifurcated at the suggestion of the tribunal following the 2018 judgment inAchmea.

The tribunal had dismissed Spain’s objection in its arbitral award, stating that the arbitration was not a dispute between “a contracting party” of the ECT and “an investor of another contracting party,” as required inArticle 26 of the treaty. The tribunal held that the fact that the EU itself is a contracting party to the ECT and that Denmark and Spain are both EU Member States “does not affect the reality” that the countries are contracting parties in their own right.

Followed by Spain, a German court has also declared twoICSID claims as inadmissible because they are incompatible with the EU law and are fundamentally not arbitrable based on the ruling of ECJ inAchmea, Komstroy, PL Holdings andMicula. Worth to note that this will have no impact on the pending ICSID proceedings between the two German companies and the Netherlands. The tribunal is free to make its own decision on the jurisdiction and validity of the arbitration agreement.

Practical Implications

After the two back-to-back inadmissibility of arbitrations on the grounds of the supremacy of EU Law, it appears that in any event, when the seat of arbitration is an EU Member State, the applicable law to the issue of jurisdiction will be EU Law. WhatKomstroy has done is given admittance to the fact that ECT is to be construed as a bundle of bilateral obligations, and therefore, it is barred from imposing any obligations from one Member State onto another. This high threshold set by the CJEU exists because of an explicit constitutionalized system which is established by the EU law to govern the relationship between its Member States. Additionally, it exists also to protect this relationship between the Member States against apparent threats that intra-EU investment arbitration poses to the said constitutionalized system. Meanwhile, the tribunalinGreen Power laid down a distinction between ICSID and non-ICSID arbitrations whereby it stated that ICSID arbitrations are delocalized, and national law is inapplicable to any part of such arbitral proceedings. Based on this distinguishing feature alone, the majority of claimants will opt for ICSID arbitration to bypass the intra-EU objection.

It is pertinent to note at this step that such decisions are bound to create inconsistency in the investment arbitration practice. At this stage, it is entirely dependent upon the arbitral tribunals seated in the EU Member States whether they continue to apply EU law to the jurisdictional inquiry. Nonetheless, the investment arbitration industry is unhindered by such developments and marches on with intra-EU claims and investment arbitration proceedings. This is major because of the belief that arbitrators will continue to claim jurisdiction over intra-EU disputes and, therefore, investors will continue to file their claims.

The critical issue is not of arbitrators granting jurisdiction over energy investment disputes, moreover of the fact that with the established jurisprudence in place, enforcement of awards can no longer happen in the EU as the national courts are bound by ECJ’s ruling. Alternatively, the investors will turn towards enforcement of awards outside of the EU to claim their damages in whatever percentage. It is indescribable what damage could this dramatic turn of events do to the trust of nationals of a country or even the image of the international institutions.

Conclusion

On one end, there are the existential crises of the EU’s constitutionalized system and, on the other, the future of ISDS. Consequently, CJEU and investment tribunals have competing interpretative authorities. When we perceive the issue from the EU’s end, based on the jurisprudence and the principle of autonomy, ECTs are inapplicable in an intra-EU setup. On the contrary, from the investment arbitration perspective, the arbitral tribunal is free to exercise jurisdiction over intra-EU BITs until the agreements are terminated. Also, what remains interesting to see is how the non-ICSID tribunals will approach the intra-EU objection in intra-EU investor-State disputes seated outside the EU. Cross-Border investment amongst the EU Member States not only diversifies services but also creates opportunities for financing infrastructure and projects. Therefore, the EU needs to establish a favourable intra-EU investment environment is required to maintain a high standard of the investment climate.

Incidentally, onJune 24, 2022, the contracting parties to the ECT met for the Ad hoc meeting of the Energy Charter Conference, confirming the agreement (in principle) on the modernization of ECT. As part of the changes, an article giving effect to theKomstroy ruling would be introduced. It is unclear whether the codification of intra-EU objection is applied retrospectively or prospectively. Nonetheless, the battle persists between the consistency and uniformity of the EU law and the maintainability of international rules and norms.

Disclaimer

The views, thoughts and opinions belong solely to the authors. Authors reserve the right to depart from these views.

About the Authors

Ms. Chandrika Sharma is an arbitration practitioner and licensed attorney in India, specializing in dispute resolution and commercial litigation. She recently completed her LL.M in International Commercial Arbitration Laws from Stockholm University.

Mr. Abeer Tiwari is a 4th year B.A. LL.B student from Balaji Law College, Pune, and an Associate Editor at IJPIEL.

Editorial Team

Managing Editor: Naman Anand

Editors-in-Chiefs: Muskaan Singh and Hamna Viriyam

Senior Editor: Aribba Siddique

Associate Editor: Abeer Tiwari

Junior Editor: Kaushiki Singh

Preferred Method of Citation

Chandrika Sharma and Abeer Tiwari, “(In)-Arbitrability of Intra-EU Disputes under the Energy Charter Treaty” (IJPIEL, 19 September 2022)

<https://ijpiel.com/index.php/2022/09/19/in-arbitrability-of-intra-eu-disputes-under-the-energy-charter-treaty/>

Recent Comments