Eleven years ago, India introduced the National Litigation Policy 2010 (“NLP 2010”) with the intention of reducing government litigation in courts by transforming government into an “efficient and responsible litigant”. [1] To what extent has the government been successful in its endeavour? By its own admission, not particularly. The Action Plan to Reduce Government Litigation 2017 (“Action Plan”) admitted that government remains the biggest contributor to the ever-increasing pendency of cases with 46% of total pending cases pertaining to government and government bodies. [2] Pendency has only increased since then, [3] with COVID-19 making matters worse as courts could not work with a full caseload. [4]

Interestingly, the government seems to have adopted a data-driven approach to analyse pendency through the LIMBS (Legal Information Management and Briefing System) portal. [5] This makes sense. It is impossible to adopt a “one size fits all” approach to the issue since such unverified pendency numbers represent litigation by and against all government bodies – central and state government ministries and departments, central and state public sector undertakings, and other government authorities. [6] A data driven approach will ensure that both macro-level and micro-level judicial data is available in a transparent manner to the government as well as the general public. This will allow stakeholders to identify what is going well and what needs to be improved in terms of judicial processes at every judicial level and every stage of the litigation process. For example, some have raised the question of whether the government is a compulsive litigant or a habitual defendant, with some studies showing that the bulk of litigation involving the government is actually filed against the government. [7] How can we answer this question without data regarding the number, nature, types and outcomes of such cases at every judicial level and at every stage of the litigation process?

However, there is little publicly available data on LIMBS or otherwise, which limits the possibility of analysis by independent researchers and the general public. [8] Left to their own devices, researchers have adopted a granular approach – a recent example is an extremely interesting and insightful analysis on the LEAP blog on litigation in public contracts. [9] The LEAP Report crunches the numbers from 13 years of cases from the Delhi High Court and their findings seem to be more or less in line with practical experience.

In this article, we will analyse the findings of the LEAP Report. This will help us understand the extent to which contractual litigation involving the government affects pendency (the answer: not much) and what the government can do to reduce such litigation further (the answer: a lot). First, we will start with the NLP 2010 to understand exactly how the government intends to reduce pendency and transform into an efficient and responsible litigant. Next, we look at the LIMBS portal to see what data is publicly available in this regard. Moving on, we summarise the LEAP Report and finally examine its findings regarding litigation in public contracts to determine how far the government has succeeded in its transformation into an efficient and responsible litigant at least in this respect.

1. National Litigation Policy 2010 – Paved with good intentions…

NLP 2010 recognizes that the government is the “predominant litigant” and aims to transform itself into an “efficient and responsible litigant”.

It explains that being an efficient litigant means a “litigant who is represented by competent and sensitive legal persons: competent in their skills and sensitive to the facts that Government is not an ordinary litigant and that a litigation does not have to be won at any cost”. To this effect, an efficient litigant should focus on the core issues in the litigation, conduct litigation in a time-bound manner and ensure that good cases are won while bad cases are not needlessly prolonged.

Similarly, a responsible litigant means that litigation will not be resorted to for the sake of litigating. As such, false pleas and technical points shall be discouraged, correct facts and relevant documents will be admitted and there will be no attempt to mislead any court or tribunal. To this end, the government must cease to be a compulsive litigant.

To ensure accountability at all levels, it aims to ensure critical appreciation of how cases are conducted. Hence, it provides that good cases which have been lost must be reviewed to ascertain responsibility so that suitable action can be taken.

It is often said that the road to hell is paved with good intentions. [10] This self-defeating exercise would be a case in point. The fact that there is no review to ensure that bad cases are not needlessly prolonged but there is a review to ensure that good cases are not lost will only incentivise government officials to appeal/challenge all cases to the highest levels as a matter of principle in the pursuit of blamelessness. [11]

To be fair, NLP 2010 does lay down guidelines for filing of appeals in Tribunal matters, service matters, revenue matters, etc. Specifically, it provides that appeals will be filed in the Supreme Court only if it (a) involves a question of law; (b) if it involves a question of fact, the conclusion of the fact is so perverse that an honest judicial opinion could not have arrived at that conclusion; (c) where public finances are adversely affected; (d) where there is substantial interference with public justice; (e) where there is a question of law arising under the Constitution; (f) where the High Court has exceeded its jurisdiction; (g) where the High Court has struck down a statutory provision as ultra vires; (h) where the interpretation of the High Court is plainly erroneous. In each case, there will be a proper certification of the need to file or not file an appeal with cogent reasons recorded in support.

Again, this seems to be a case of good intentions. While it makes sense to lay down guidelines to restrict filing unnecessary appeals, the fact that the guidelines are so broad and vague completely defeats the purpose. The fact that reasons must be recorded in writing for filing or not filing an appeal will – once again – only incentivise government officials to appeal all cases to the highest levels as a matter of principle in the pursuit of blamelessness.

When it comes to alternative dispute resolution, NLP 2010 notes with approval that more and more government bodies are resorting to arbitration. This must be encouraged at every level while emphasizing that arbitration should be cost effective, efficacious, expeditious, and conducted with high rectitude. Disputes regarding the appointment of arbitrators and arbitrability – which results in prolonged litigation even before the start of arbitration – should be avoided through more precise drafting of arbitration agreements.

NLP 2010 specifically recognizes that unfavourable arbitration awards are almost invariably challenged even though these objections lack merit. Hence, it clearly provides that routine challenges to arbitration awards must be discouraged and reasons to challenge awards must be clearly formulated before the decision is made to challenge such awards. All well and good – but without any clear enforcement mechanism.

This is a recurring feature of NLP 2010. While it is paved with several good intentions (ensuring that government advocates are well chosen and well-trained, unnecessary adjournments are avoided, pleadings are carefully and precisely drafted, appeals are filed only in accordance with guidelines, delayed appeals are avoided, alternative dispute resolution is encouraged, etc), it fails to enforce such good intentions through appropriate mechanisms. Wherever mechanisms are instituted, these would often have the tendency to worsen the problem rather than solving it.

Unfortunately, a more detailed critique of NLP 2010 is beyond the scope of this article. However, it seems that government is aware that NLP 2010 leaves much to be desired. There have been reports that it has been under review since as early as 2015 [12] and as late as 2021 [13] without any positive outcome.

2. LIMBS – Knowing what the other arm is doing…

LIMBS is a government portal that allows all arms of the government to know what the other arms are doing in terms of litigation management. However, there is no way for the general public to access or verify the data in LIMBS. All that the general public can see is a few statistics and graphs. For example, LIMBS states that pendency is at 484,336 although it is unclear how this is calculated. Of these, 25,957 cases are shown as pending compliance although it is unclear what that means. Similarly, contempt cases are shown as 2065 and important cases as 975 even though there is no way to understand what this refers to.

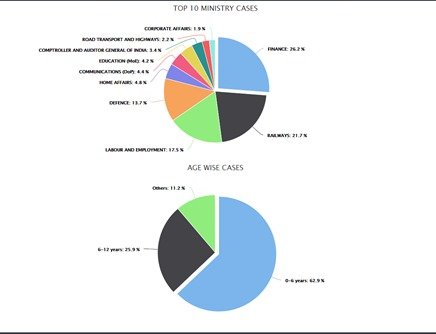

Image 1 below shows ministry-wise cases with Finance being the clear winner (121,476 cases) with Railways (99,551 cases), Labour and Employment (77,117 cases) and Defence (63,162) being major contributors.

Image 1: Ministry-wise cases

Image 2 purportedly shows Top 10 Ministry cases and age-wise cases. It seems that Finance (26.2%), Railways (21.7%), Labour and Employment (17.5%) and Defence (13.7%) are the major contributors once again. However, it is difficult to understand what these numbers mean.

Image 2: Top 10 Ministry cases and age-wise cases

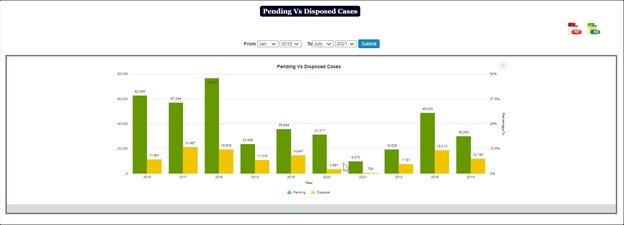

Image 3 purportedly shows pending vs disposed cases between 2012-2021. While it is badly arranged, the only takeaway seems to be that pending cases have increased significantly and disposed cases have been unable to keep pace.

Image 3: Pending vs Disposed Cases

While it is entirely possible that this makes sense to those who can access LIMBS data, the general public must make do without knowing how the various limbs of government are faring in terms of litigation management.

3. LEAP Report – One small step for legal researchers…

In this background, the LEAP Report is even more significant – by itself, it is a small step towards data driven analysis of judicial decision making. In context – as one of the first attempts of its kind – it represents a giant leap in the field. [14]

So, what are the more interesting findings of the LEAP Report?

1. It starts with a dataset of 5,42,355 cases filed before the Delhi High Court from 1 January 2007 until 30 September 2020. It then undertakes three rounds of data filtering to arrive at a subset of cases that are the closest proxies of contractual disputes involving the government.

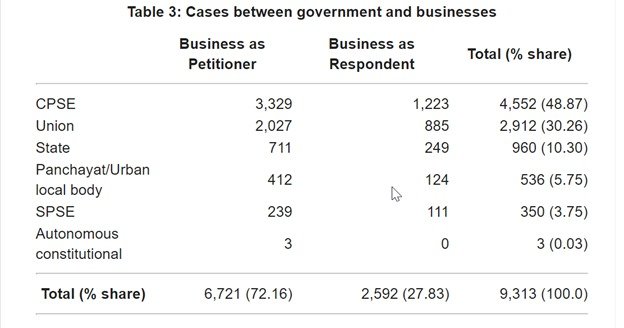

2. This filtering exercise generates a subset of 9,313 cases between businesses and the government and its agencies (Table 3) – this is mostly miscellaneous petitions (~50% thereof), followed by arbitration (~23%), civil suits (~12%) and writ petitions (~11%). This suggests that such litigation is a small proportion (about 7%) of the overall litigation involving the government.

3. 49% of such commercial litigation is against Central Public Sector Enterprises (CPSEs), 30% against the central government, 10% against the state government and only 4% against the State Public Sector Enterprises (SPSEs). Of course, these numbers may be peculiar to Delhi High Court since there are so many CPSEs headquartered in the National Capital Region.

4. Businesses initiate the bulk of the government-business contractual litigation (almost 72%).

Practical experience suggests that corporations are inherently reluctant to litigate against public customers. However, the LEAP Report findings suggest that corporations are far more litigious than the government. However, this fact on its own might be slightly misleading. There are good reasons for this imbalance.

Firstly, public procurement is conducted on “take it or leave it” terms – for very good reasons of transparency and accountability. However, the problem is that such terms significantly favour the government/buyer against the corporation/contractor. [15] Contractors are understandably reluctant to initiate litigation on such terms since the chances of success are correspondingly lower than they would be if the terms were fair and balanced.

But then why does contractual litigation against the government outweigh contractual litigation by the government? The answer is simple. The fact that the proverbial deck is usually stacked in favour of the government/buyer means that it often does not need to resort to litigation to enforce its claims while that is usually the only recourse for the contractor. Buyers in public procurement contracts have broad powers to delay and even withhold contractual payments, outrightly deny or simply delay any decision on contractual claims for time and money raised by the contractor, etc.

The situation is exacerbated by the fact that government officials are loath to take any decision which may be seen as favouring the contractor even if they privately believe that such claims are legitimate. In the pursuit of blamelessness, legitimate claims are outrightly denied or any decision on such claims is indefinitely delayed. This forces the contractor to litigate its contractual claims through arbitration. If the arbitral award is not in favour of the government, government officials feel constrained to challenge such awards through several levels before the High Court and then the Supreme Court over the course of several years.

On the other hand, the government can recover its claims by simply withholding money which would otherwise have been due to the contractor under the contract. If the contractor believes that such government claims are not legitimate, it must dispute such claims through arbitration to be successful. Heads you win, tails I lose.

Finally, contractors are always worried that litigation against the government may expose them to the Damocles Sword of blacklisting or being debarred from public tendering for a certain period. [16] Although examples of contractors being blacklisted merely for being litigious are unheard of, this adds to the fear factor simply because the stakes are so high. To add to this fear factor, public tenders often ask bidders to submit declarations of its ongoing litigations against the government as a part of the pre-qualification process. This is at best strange since such information is often confidential in nature. Why such declarations are required or how they are evaluated in the tendering process is generally unknown.

NLP 2010 clearly states that the government aims to transform itself into an “efficient and responsible litigant”. If the government truly wants to act on its stated intent of reducing litigation, a fair and balanced public procurement law and construction law is only the first step. [17] Even more critical would be to have fair and balanced public procurement contracts based on global best practices.

In many ways, this may seem contra-indicated. One might argue that having fair contracts would increase litigation by contractors since the deterrent effect of unfair contract terms would no longer apply. Quite the reverse. Fair and balanced contracts would go a long way towards an amicable resolution of commercial disputes on public contracts, thus saving both judicial time and public money. Again, practical experience suggests that the more things change, the more they stay the same. For example, the Arbitration and Conciliation Act 1996 was amended in accordance with global best practices in 2015 such that employees of one party could no longer be an arbitrator in a dispute featuring that party. This amendment was aimed at nullifying government contracts where senior government officials decided disputes against their own departments, CPSEs and SPSEs. Even now, six years later, practical experience suggests that many if not most government departments, CPSEs and SPSEs have not yet amended their contracts to change this. The end results? Even more litigation against the government. Now, contractors (who are constrained to accept such arbitration clauses in the “take it or leave it” contract) must initiate litigation simply to have such clauses declared void and have unbiased arbitrators appointed. This is supported by the finding that miscellaneous petitions account for ~50% of overall commercial litigation.

Such examples abound. For example, government procurement contracts which are funded by international agencies are mandatorily based on global standard contracts such as the FIDIC suite. Even where such global standard contracts are used, they are heavily edited with special terms and conditions to swing the pendulum back in the other direction. To paraphrase the greatest lawyer on the Discworld – “Ave, pacta novo! Similis pacta Seneca” (“Hail to the new contract! Same as the old contract”). [18]

Most critical of all, then, is to change the mindset of government officials towards government procurement. It has often been said that culture eats strategy for breakfast. As anyone who has dealt with government officials knows, lethargy eats strategy for lunch.

About the Authors

Rajarshi Sen is a lead counsel at Siemens Energy India.

Aditya Vemulakonda is a 4th Year Law student at School of Law, Bennett University.

Editorial Team

Managing Editor: Naman Anand

Editors-in-Chief: Akanksha Goel and Aakaansha Arya

Senior Editor: Jhalak Srivastav

Associate Editor: Aditya Vemulakonda

Junior Editor: Vidhi Saxena

Disclaimer

Views expressed are personal and do not reflect those of the institution with which the authors may be associated.

Preferred Method of Citation

Rajarshi Sen and Aditya Vemulakonda, “The Mystery of the Efficient and Responsible Litigant: Notes on a Data-Driven Analysis of Litigation in Public Contracts from the Delhi High Court” (IJPIEL, 31 July 2021)

<https://ijpiel.com/index.php/2021/07/30/the-mystery-of-the-efficient-and-responsible-litigant-notes-on-a-data-driven-analysis-of-litigation-in-public-contracts-from-the-delhi-high-court/>

Endnotes

[1] National Legal Mission to Reduce Average Pendency Time from 15 Years to 3 Years – National Litigation Policy Document Released, Press Information Bureau, Government of India, Ministry of Law and Justice. https://archive.pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=62745

[2] Action Plan to Reduce Government Litigation, Government of India, Ministry of Law and Justice, Department of Justice. https://doj.gov.in/page/action-plan-reduce-government-litigation

[3] Pendency of cases in the Judiciary, PRS Legislative Research https://prsindia.org/policy/vital-stats/pendency-cases-judiciary ; Roshni Sinha, Examining pendency of cases in the Judiciary, PRS Legislative Research, https://prsindia.org/theprsblog/examining-pendency-cases-judiciary , Yash Agarwal, What does data on pendency of cases in Indian courts tell us?, The Leaflet (October 03, 2020) https://www.theleaflet.in/what-does-data-on-pendency-of-cases-in-indian-courts-tell-us/

[4] Satyajit Sarna, A ticking bomb: the pendency problem of Indian courts, The Indian Express (May 25, 2021) https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/coronanvirus-pandemic-virtual-hearing-india-courts-judiciary-system-7328862/, Apurva Vishwanath, Pandemic impact: Record pendency of cases at all levels of judiciary, The Indian Express (March 27, 2021) https://indianexpress.com/article/india/pandemic-impact-record-pendency-of-cases-at-all-levels-of-judiciary-7247271/ ; The Wire Staff, COVID-19 Increased Pendency of Cases at All Levels of Judiciary, The Wire (March 27, 2021) https://thewire.in/law/covid-19-increased-pendency-of-cases-at-all-levels-of-judiciary

[5] Government of India, Ministry of Law and Justice, Department of Legal Affairs, Legal Information Management and Briefing System 2.0. https://limbs.gov.in/

[6] Deepika Kinhal, Tackling Government Litigation, The Hindu (January 13, 2018) (“Kinhal”) http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/tackling-government-litigation/article22444640.ece ; Government Litigation: An Introduction, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy (“Vidhi Report”) https://vidhilegalpolicy.in/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/GovernmentLitigationFinal.pdf .

[7] Towards an Efficient and Effective Supreme Court, Kinhal and Vidhi Report (“Vidhi Report – Supreme Court”). https://vidhilegalpolicy.in/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/TowardsanEffectiveandEfficientSupremeCourt.pdf

[8] LIMBS database is accessible only to government officials and government advocates. See Vidhi Report at supra note 6.

[9] Devendra Damle, Karan Gulati, Anjali Sharma and Bhargavi Zaveri, Litigation in public contracts: some estimates from court data (“LEAP Report”). https://blog.theleapjournal.org/2021/05/litigation-in-public-contracts-some.html

[10] Although several earlier versions are known, this version was first published in Henry Bohn, A Hand-book of Proverbs (1855). Since then, it has been used by famous authors and artists such as Charlotte Brontë, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Søren Kierkegaard, Karl Marx, Terry Pratchett, John Michael “Ozzy” Osbourne and Bruce Dickinson. https://archive.org/details/ahandbookprover01raygoog/page/n525/mode/2up

[11] By this, we are referring to the hypothesis that fear of the three Cs (Comptroller and Auditor General, Central Bureau of Investigation and Central Vigilance Commission) in government officials leads to policy paralysis. See Richa Mishra, Three Cs and the fear of policy paralysis, The Hindu Business Line (June 21, 2017). https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/specials/three-cs-and-the-fear-of-policy-paralysis/article9732194.ece Against this, others have argued that the issue is not with transparency and accountability per se but with the malicious misuse of the 3 Cs and that what is needed is in fact more transparency and accountability by the 3Cs themselves. See Archana Gulati, Reforming India’s Bureaucracy: A Multipronged Approach, The Quint (July 26, 2016). https://www.thequint.com/voices/opinion/reforming-indias-bureacracy-a-multipronged-approach#read-more The procedures for departmental disciplinary proceedings have been laid down in different sets of rules applicable to Government servants. The rules having the widest applicability are the Central Civil Services (Classification, Control & Appeal) Rules, 1965. Chapter VII of the Central Vigilance Commission’s Vigilance Manual 2017 deals with disciplinary proceedings and suspension. A more detailed analysis is beyond the scope of this article.

[12] Press Trust of India, Secretaries’ panel clears litigation policy, The Business Standard (June 5, 2015). https://www.business-standard.com/article/pti-stories/secretaries-panel-clears-litigation-policy-115060400439_1.html

[13] Drafting of revised National Litigation Policy underway: Centre informs Delhi HC, Asian News International (January 13, 2021). https://www.aninews.in/news/national/general-news/drafting-of-revised-national-litigation-policy-underway-centre-informs-delhi-hc20210113150307/

[14] Supra note 7.

[15] For a more detailed analysis of onerous clauses in construction contracts, see Ganesh Chandra Kabi and Mitali Kshatriya, Checks on Unfair Terms in Construction Contracts: Examining the Current Legal Landscape, IJPIEL (October 7, 2020). https://ijpiel.com/index.php/2020/11/27/checks-on-unfair-terms-in-construction-contracts-examining-the-current-legal-landscape/

[16] For a more detailed analysis of the framework for blacklisting of companies by government, see Nadiya Sarguroh and Gunjan Shrivastav, Need to Relook at the Framework for Blacklisting of Companies in India (IJPIEL, 9 April 2021). https://ijpiel.com/index.php/2021/04/08/need-to-relook-at-the-framework-for-blacklisting-of-companies-in-india/

[17] The Public Procurement Bill 2012 was introduced to regulate and ensure transparency in procurement by the central government and its entities. For a more detailed analysis, see The Public Procurement Bill 2012, PRS Legislative Research. https://prsindia.org/billtrack/the-public-procurement-bill-2012 For a more detailed analysis of the need for a construction law, see Amit Kathpalia, Does India need a Construction Law? IJPIEL (May 6, 2021). https://ijpiel.com/index.php/2021/05/06/does-india-need-a-construction-law/

[18] Terry Pratchett, Night Watch, Doubleday, UK 2002. In the original, the phrase used is “Avé! Duci Novo, Similis Duci Seneci!” and “Avé! Bossa Nova! Similis Bossa Seneca!” – both are variants on a theme of “Hail to the new boss! Same as the old boss!“

Recent Comments